The Last Voyage Of Bill Tilman

Book Extract

The loss of an old converted Dutch steel tug in the South Atlantic in 1997 and the loss of six young men would have made few headlines in the UK press had it not been for the fact that also on board was the famous 80-year-old indomitable mountaineer, adventurer, explorer and ocean voyager, Major H W ‘Bill’ Tilman.

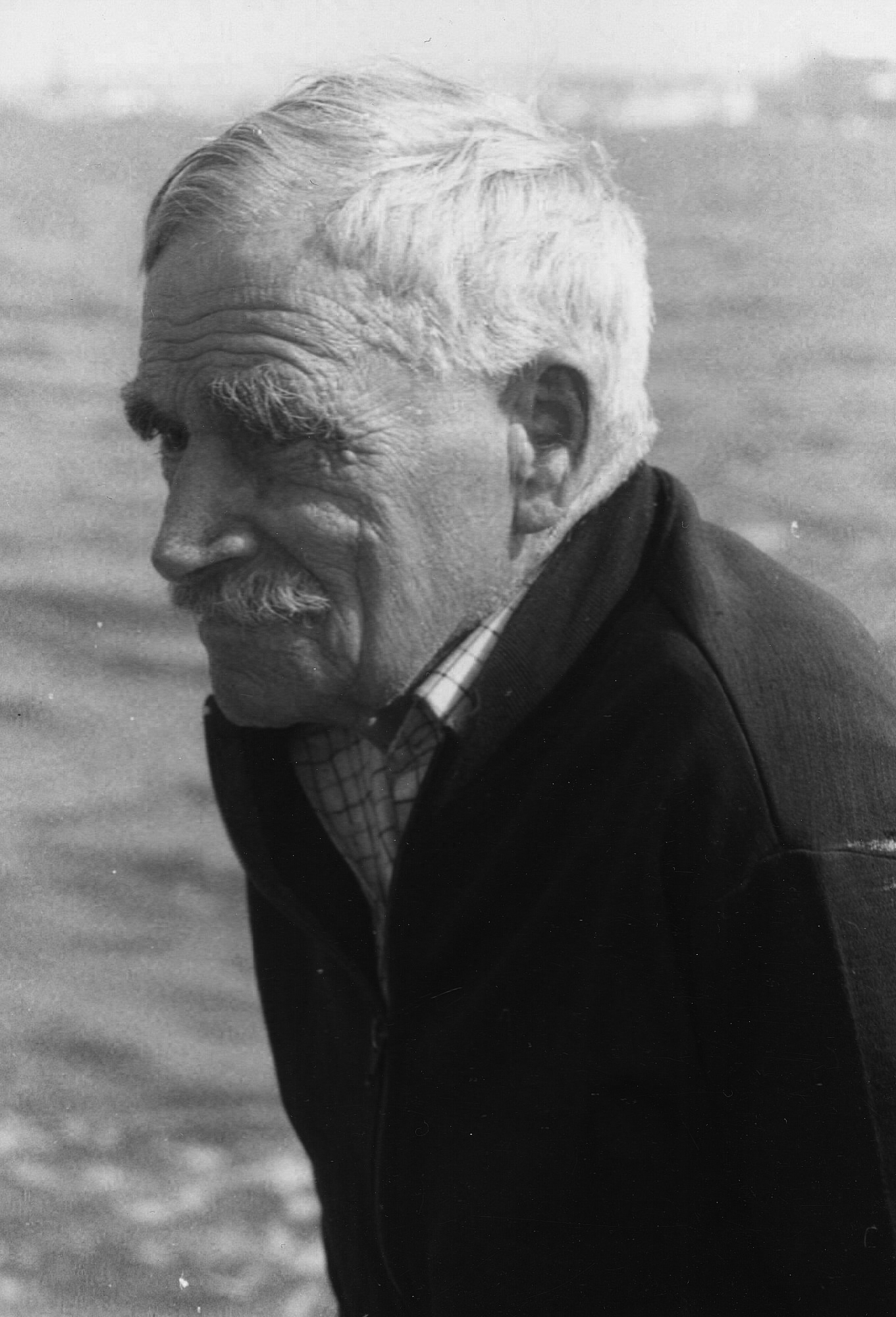

Bill Tilman on board En Avant

Little of this story and the reason why Tilman, at the age of 80, had shipped as crew on a vessel headed for Antarctica, owned and skippered by a young Englishman, Simon Richardson, would ever have been known had not Simon’s mother, Dorothy, written an account of the incident and of her son’s brief life entitled The Quest of Simon Richardson.

I first met Bill Tilman in 1961 when he answered an advertisement I had placed in Yachting Monthly seeking a sailing adventure during my gap year before University. He asked me if I wanted to join his Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter Mischief as part of the crew for a proposed trip to Baffin Island. I was intrigued and spent some time on board Mischiefwith the old man in Lymington and helped him with the fitting out of the boat for his trip. To my eternal regret I eventually turned down his offer.

Tilman did not envisage returning to the UK until November and I was due to start at St Andrews University in Scotland that September. Had I had more guts I should have accepted Tilman’s rather vague offer to put me ashore somewhere in Greenland in good time to get me back for the start of the university term. When I did get to St Andrews I was told that I could have met up, and had a lift back home, with a student expedition from the university which was spending the summer in the research hut which St Andrews maintained on the west coast of Greenland. Tilman and Mischief later that year did in fact meet up with them. Dr Harold Drever, who was leading the expedition, was an old friend of Tilman’s and he later taught me geology at St Andrews. A year later, Dr Drever told me that he was surprised that I was not on board Mischief when they met up in Greenland as Tilman had told him he was going to have a St Andrews student on board for the trip to Baffin Island. To this day I don’t know why Tilman never said any of this to me but he was never a good communicator and maybe he thought that it wasn’t his place to assist me in my decision whether to go or not. But it was a crying shame.

On a voyage to Greenland in 1973 on the decrepit pilot cutter Baroque (described in Tilman’s book Ice With Everything) Tilman shipped with him, as part of the usual motley crew, a young Englishman called Simon Richardson.

Simon was 20 years old, the son of a Southampton solicitor. He was educated privately at Winchester College and had spent a year reading civil engineering but left his college after a year.

He was impatient, wanted to start living his own life and was not really academically minded. He was extremely practical and mechanically inventive and preferred a life of action using his hands. To gain sailing experience he signed on for several long-distance yacht delivery trips and then fell in with a man doing up an old German E boat in Italy. Simon helped him for a while, then took passage on a boat travelling through the French canals.

Back in England he applied to join the British Antarctic Survey. Before he received a reply, he saw an advertisement in The Times, inserted by Tilman, seeking crew for a voyage to Greenland.

Simon jumped at the chance.

Simon joined Baroque at Mylor on the River Fal in Cornwall in May 1973 and soon established himself as the most capable member of the crew. His mechanical and inventive skills were soon put to use as the boat was, basically, falling apart. It was mainly through Simon’s efforts that Baroque made it to Greenland at all.

Tilman was renowned as an irascible and difficult character regularly falling out with his crews, who generally ended up loathing him and vowing never to ship with him again. (On one earlier voyage in his first ship, Mischief, the crew mutinied in South America and walked ashore.) With Simon, however it was different. Tilman saw something in the young man, appreciated his efforts and attitude, and a relationship of sorts developed between them. Tilman said later that he had picked a winner in Simon and he found him active, energetic, knowledgeable about boats and engines and a thorough seaman. Simon also got on with the other crew members and the voyage became one of Tilman’s happiest and most successful, despite the condition of Baroque. She leaked like a sieve, the port chain plates soon pulled out, the sails were old and rotten, the engine kept failing and the bulwarks up forward disintegrated.

Simon’s father died following a stroke and Simon, deeply affected, felt he should get a proper job. Simon soon obtained a job in Scotland building a new harbour and plant for offshore oil rigs. This was dangerous but well paid work during which he learnt his skills as a welder. In October 1974, just as work on the harbour was coming to an end, Simon suffered a serious injury to one of his legs. He was knocked off the quay by a crane and landed on the steel deck of a ship 17 feet below. His right leg was shattered just above the ankle. He was in hospital in Greenock for a month, where he was told that he would never walk again unaided. Convalescing back at home in Hampshire he had further treatment and after a few weeks was, in fact, able to start walking with the help of crutches.

Simon was now 23 and, during his recuperation, began to develop the plan he had first dreamt up on his Greenland trip: to sail to Smith Island in Antarctica, part of the South Shetland Islands, and to climb Mount Foster, the highest mountain in the region. Such an expedition was fully in the tradition of Tilman’s voyages and had, in fact, been attempted by Tilman himself in 1966, in Mischief. That was the only voyage on which Tilman had lost a man overboard.

The main problem, however, was that Simon did not have a boat and had little money. Simon reckoned that, by using his welding skills, he could afford to buy and convert one of the decommissioned working vessels which were being offered for sale in Holland. He bought for £750, sight unseen, an 18 metre steel tug which had been involved in a serious marine accident, leaving the boat sunk and one crew member dead. She had been refloated but much work was needed. She had no engine, no accommodation and would need to be adapted to take a mast and sails. The boat was called En Avant.

Simon moved to Holland and started work on the boat, even though his leg was still in plaster and he needed two sticks to walk.. He installed a second hand diesel engine which he had brought over from England, fitted out some basic accommodation below, added a mast for a gaff rigged sail and welded on a hollow steel box keel to help with her sailing ability.

Back in England, work continued throughout the winter.

Simon had, by this stage, asked Bill Tilman if he wished to join the expedition. Tilman, after a disastrous voyage in Baroque to Spitzbergen during which he had been forced to abandon his boat in Iceland, went to visit Simon and the tug. He remained non-committal but Simon was adamant that he wanted Tilman on board.

By April work was as complete as it ever would be but Simon still had no crew, except for an old school friend who had agreed to come along. He was Mark Johnson, a merchant seaman.

Tilman was away bringing Baroque back from Iceland and had still not made a decision. En Avant had to leave by late July if they were to get to Smith Island before the onset of the Antarctic winter.

Simon put an advertisement in The Times – ‘crew wanted for Antarctic voyage’ – which elicited 168 replies over a four-day period. From these Simon selected three, Rod Coatman, Robert Toombs and Charles Williams. Later, an American climber Joe Dittamore agreed to come; he said he knew of a New Zealand climber who could join them in the Falkland Islands.

In May, Tilman arrived back in England, sold Baroque and told Simon he would like to join them. It was to be Tilman’s 80th birthday that year and Simon remembered a night watch discussion during his voyage in Baroque when Tilman expressed his wish to spend his upcoming birthday at sea in polar waters.

The question arises as to why Tilman, a superb seaman, would agree to go to sea in such a seemingly unseaworthy vessel. The answer probably lies in the fact that, by then, Tilman had little to look forward to. He could no longer command his own vessel, his beloved sister with whom he had shared his house in Barmouth had recently died, as had his favourite dog. He was finding it difficult

to walk the fells and hills above his house. How else could he now get to sea and what better way to celebrate his life than by spending his birthday on an expedition to Antarctica? If he ever thought about the state of the ship, maybe he was willing to accept the risk as reward for one last adventure.

Even after the conversion, the En Avant remained extremely tender. She had very low freeboard and no guardrails fitted around the sides. She rolled excessively. She had very poor sailing qualities, which were never properly tested before the departure.

En Avant sets sail

En Avant departed Southampton on 9 August 1977, with seven people on board. Tilman soon learnt to fit in and became quite fond of the young crew and their ways, and never interfered with the running of the ship. En Avantreached the Canary Islands at the end of August after a relatively easy downwind passage. From there they motor sailed to Rio de Janeiro. They arrived on 29 October.

En Avant set sail in November for the Falkland Islands, where they were to pick up two New Zealand climbers. In Simon’s last letter to his mother he says: ‘six weeks to Port Stanley where the natives should be friendly.’ En Avant never arrived in Port Stanley and was never seen again.

A search was begun on 9 January 1978. All British Antarctic Survey ships were asked to keep a lookout and the Argentinian and Chilean air services were informed. Neither the vessel nor any of her crew nor any wreckage has ever been found.

Much speculation has been aired as to the cause of the loss. It is most likely that the boat was simply overwhelmed and foundered through stress of weather. Tugs, even when converted, are notoriously unhandy, have very low freeboard and are tender.

Tragic though the loss of En Avant was, it at least granted Tilman his wish not to die in his bed.

© Not to be reproduced without written permission from Fernhurst Books Limited.

Last Voyages is written by Nicholas Gray. Nicholas Gray has sailed all his life and owned 14 boats. He raced trimarans short-handed and has competed in the Round Britain & Ireland and Azores and Back races, winning his class in both. During this time he competed against many of the sailors featured in this book. He has worked in Merchant Banking, as a solicitor and in the petroleum industry. He has also had an interest in a sailmaking company and owned a boatyard specialising in the restoration of classic wooden boats.