Course To Steer: The Basic Plot

Book Extract

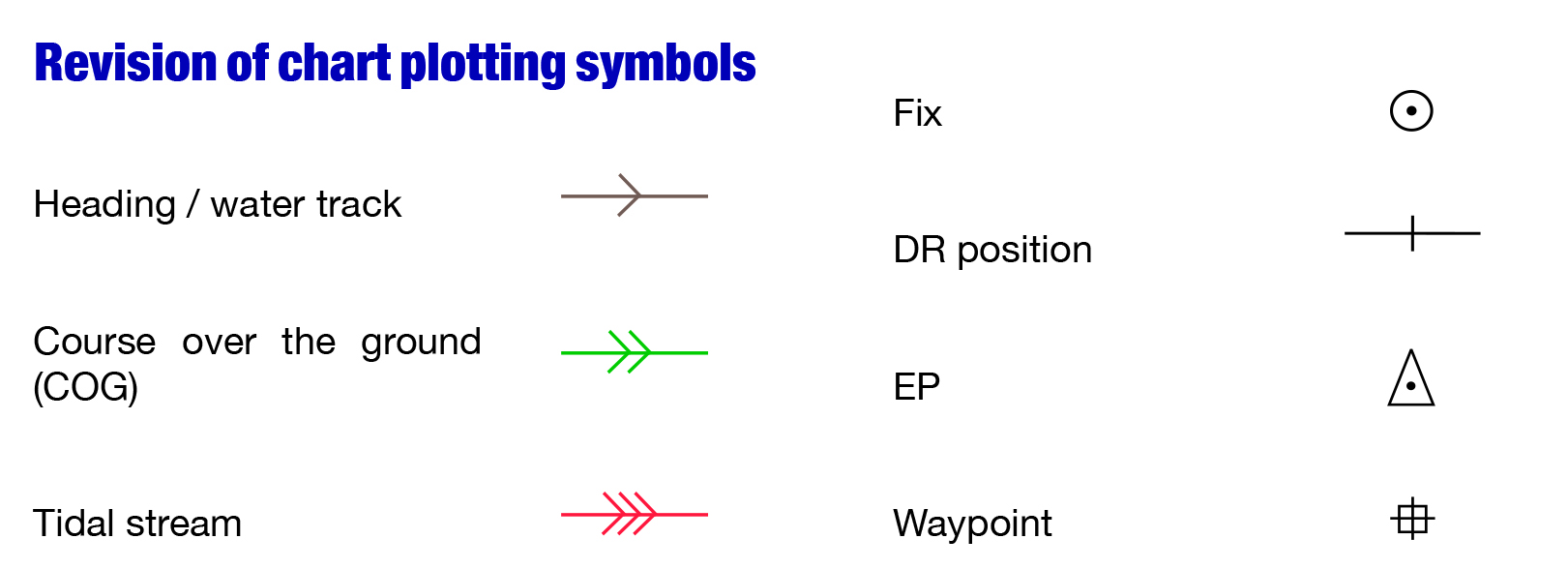

From the chartwork point of view, calculating and understanding a course to steer is perhaps the most important and most regularly used part of navigation. A course to steer is vital, to make navigation safe and efficient.

Although at first glance the diagram may look a little similar to an EP, the purpose of the calculation is completely different. An EP is one of a range of methods of checking the boat’s position, to answer the first question in navigation “Where am I?” GNSS is used more frequently than an EP (or any other method) to check the position, because it is quick and generally reliable, but there is only one way to answer the second question, “Where should I go now?”, and that is the course to steer.

A course to steer is unique because it involves predicting the course that will take the boat to a chosen position. It takes into account:

- The tidal stream that will be experienced

- The estimated speed of the boat

- Any leeway

A course to steer is calculated in advance; it is a form of pre-planning, adjusting the way the boat is heading before setting off to prevent the tidal streams and the leeway from pushing the boat off the desired track. A basic GNSS set cannot do this. If the destination is put into the GNSS as a waypoint the set will calculate the direction towards it and keep updating that as the boat moves, but it will not take into account the tidal streams, because the set does not have that information. The boat may be pushed away from the track, possibly into a dangerous situation. Remember that GNSS is a great aid to navigation but essentially it is a position-fixing device. After the skipper has calculated a course to steer the GNSS can be invaluable for checking that everything is going well while the course is sailed. In fact, without GNSS, if there is nothing on which to take a bearing, it can be impossible to check a course to steer. The skipper may only know that they are wrong when the buoy fails to appear!

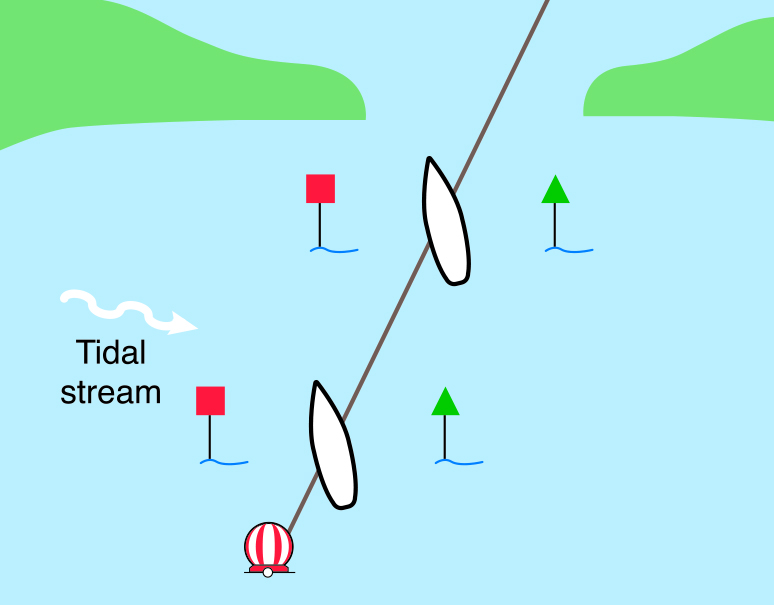

The principle of a course to steer is easy to see when a boat is steering into the entrance of a marina where there is a strong crosstide.

The experienced helmsman can see and feel that the boat is being pushed sideways by the tidal stream, and will instinctively head up into the tidal stream to compensate (Figure 47).

Course to steer in a tidal stream

If they can see that altering the heading alone is not sufficient the experienced helmsman will increase the speed. The speed of the boat is obviously significant, especially a lack of speed when the sideways effect of the tidal stream will be felt more strongly. These adjustments to the heading and speed are often made by eye, or by following markers put up to form a transit.

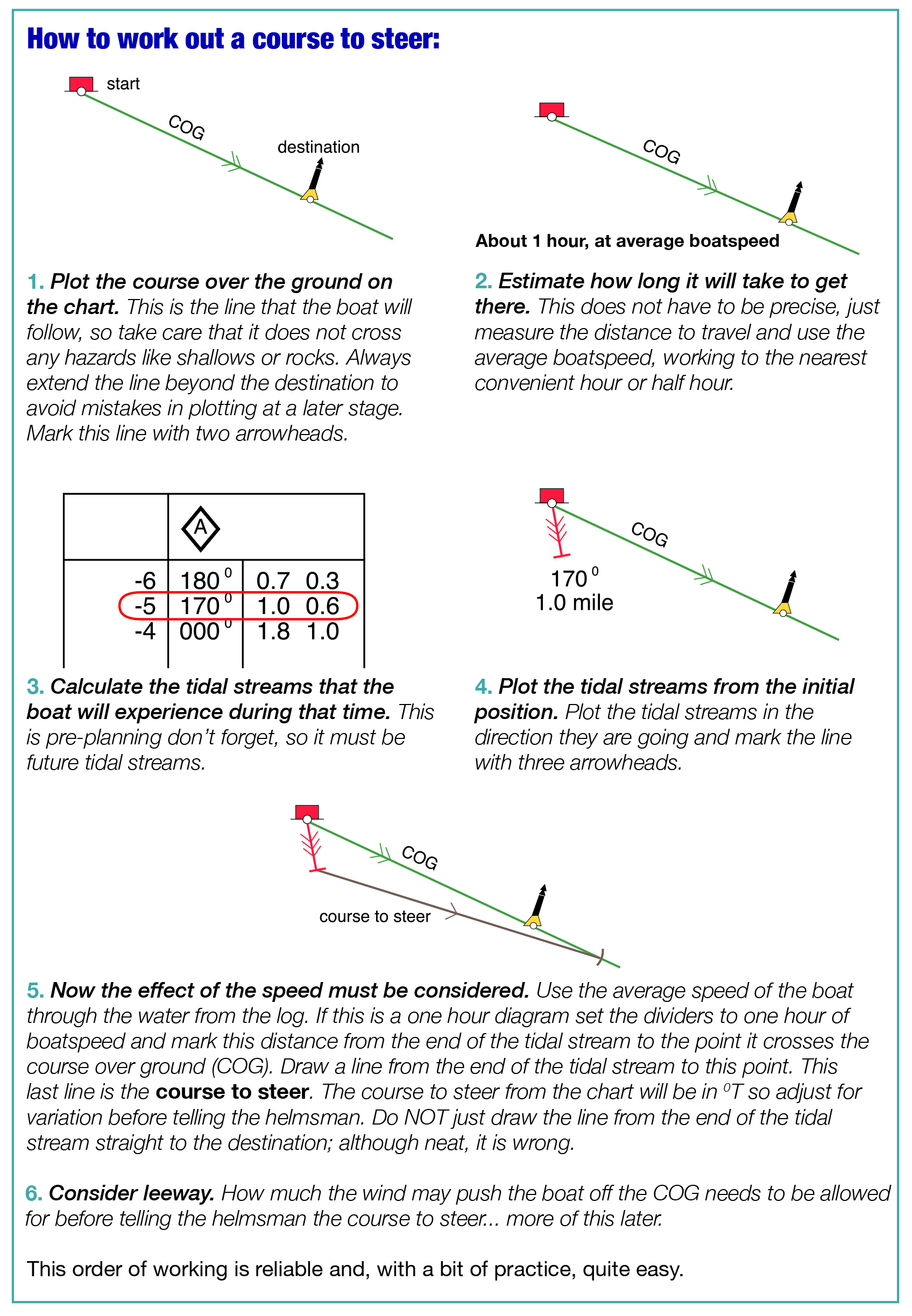

How to work out a course to steer

A course to steer is really just the same but, without the posts and the narrow entrance ahead, the effect of tidal stream cannot be seen and the allowance made by eye. The tidal stream must be calculated using the tidal diamonds on the chart or the tidal stream atlas and the speed of the boat must be taken into account. The basic method of calculating a course to steer is very straightforward and needs to be worked out in good time, before the boat arrives at the position where the skipper intends to alter course. Once at that position the crew will ask, “What’s the next course, skipper?” and the skipper needs to be ready with an answer. “Er, well I’m not sure” will not inspire them with confidence.

I heard a skipper say once, “Sail round the buoy while I work it out.” Not a good idea! (See page 59.)

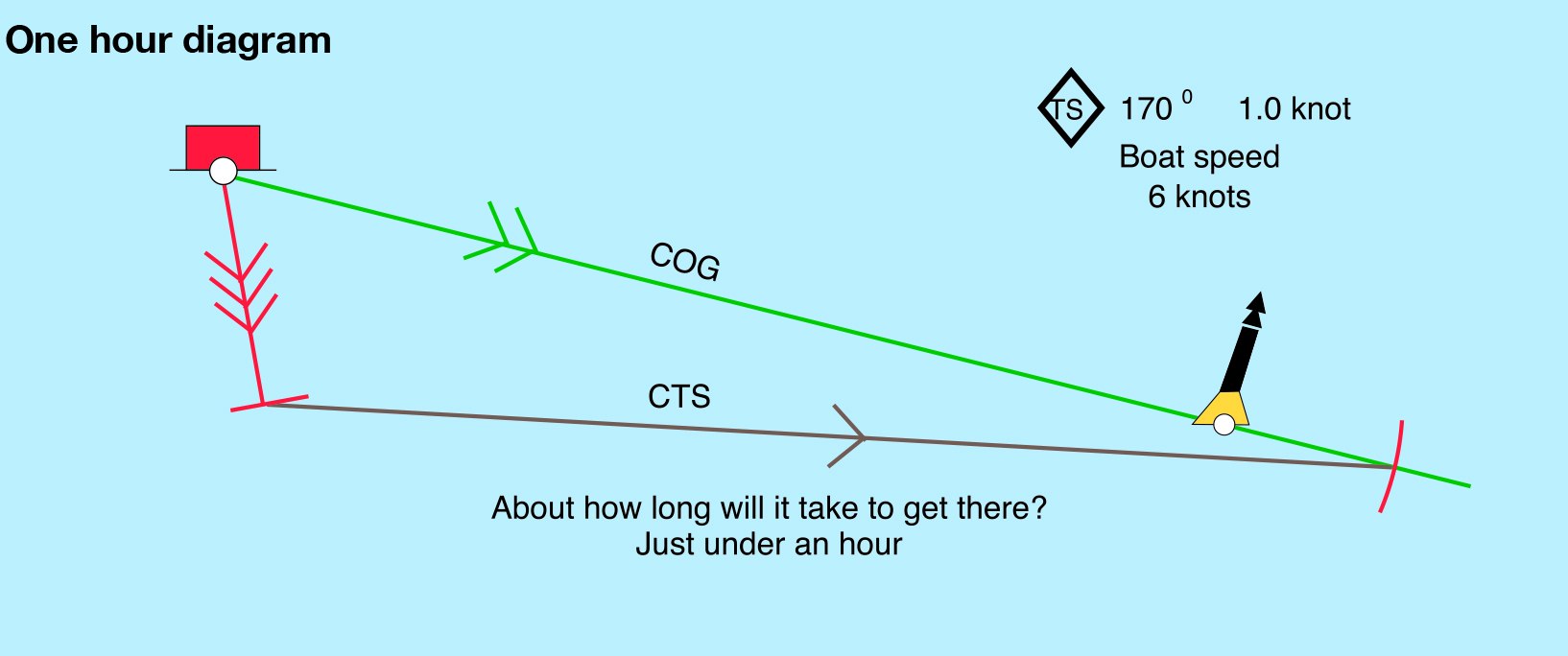

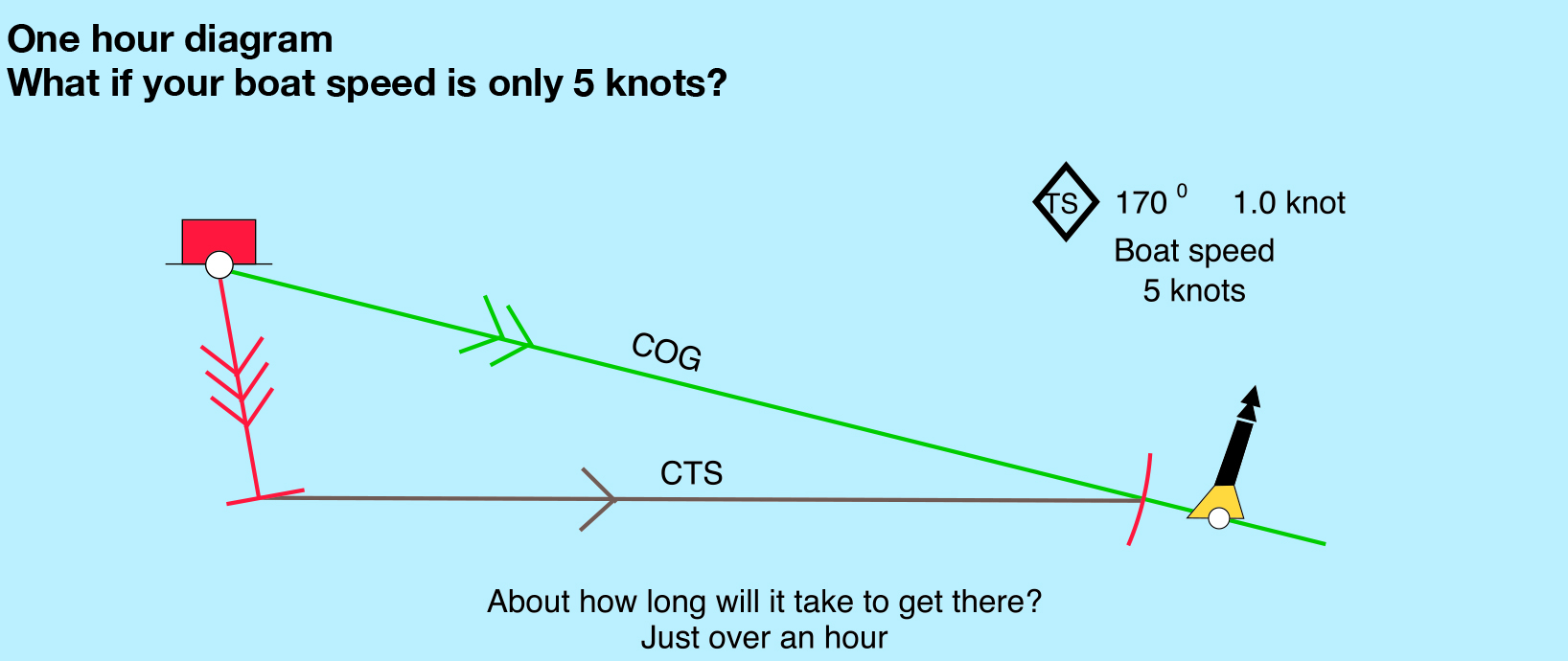

Additionally, just a quick look at the finished diagram should be enough to see approximately when the boat will arrive.

A rough estimated time of arrival (ETA) is quite good enough usually, and useful too. It avoids skippers worrying when they cannot see the next buoy ages before it will be visible and allows time for a cup of coffee! (See Figures 48 and 49.)

One hour diagram to give a rough ETA

ETA if the speed is slower

Many skippers plan their trip using the buoys as marks along the route. This is fine, but remember that buoys can be a little off their charted position. Also, although using a buoy is convenient because it is easy to know when you have found it, and the buoy gives the skipper a fix of position, be cautious. In poor visibility or in the dark the boat could come dangerously close to a very solid object. Motor cruiser skippers often set the waypoint near, but not dead on, the buoy because of their speed.

OK, so plotting a course to steer is easy; follow the steps and you cannot go wrong.

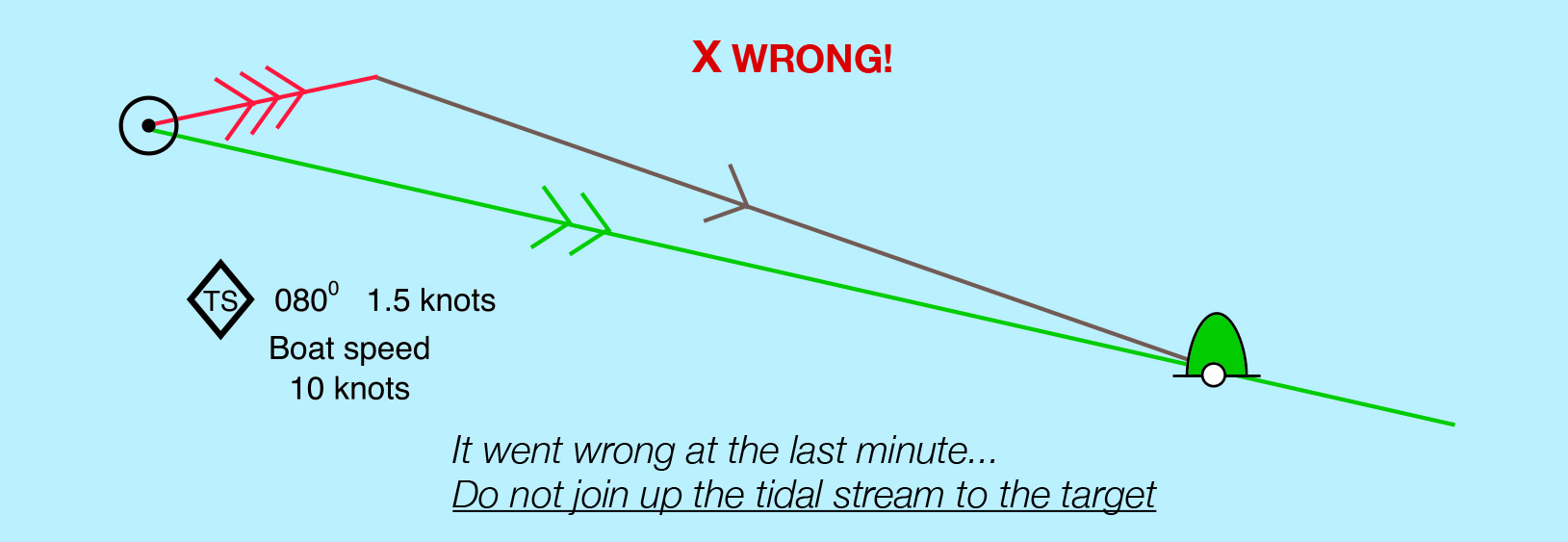

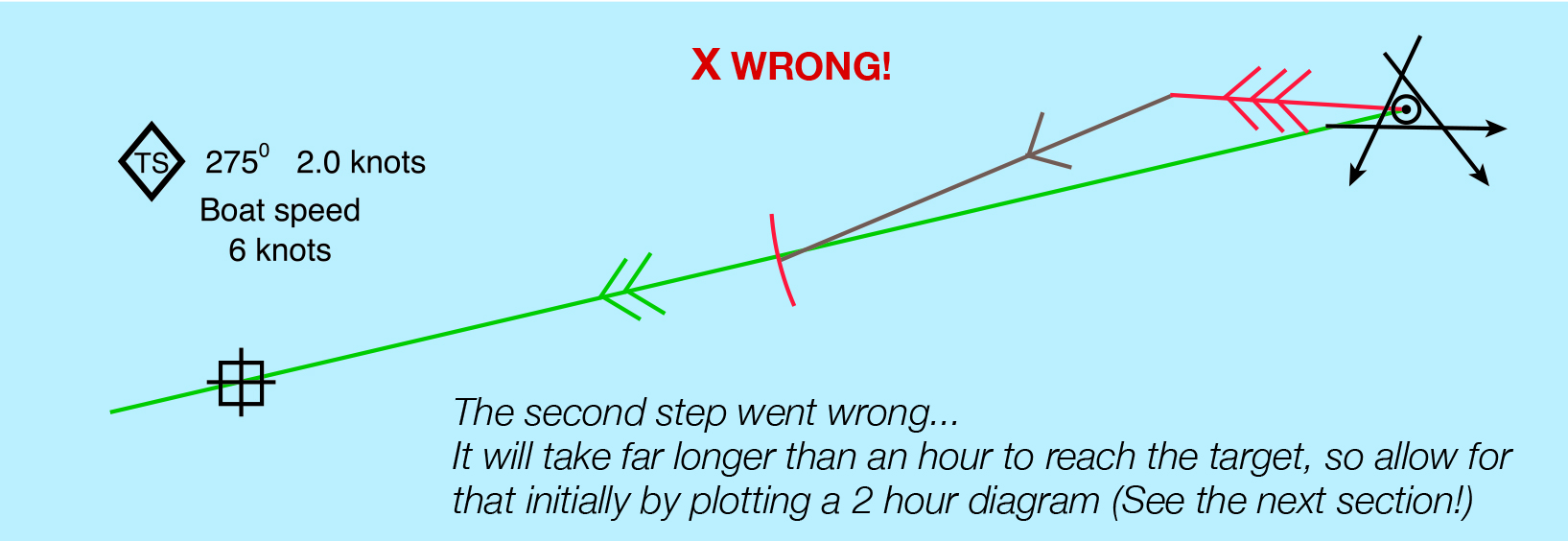

So… what has gone wrong with these diagrams below?

Error in plotting a course to steer: joining up to the target

Error in plotting course to steer: using the wrong time period

© Not to be reproduced without written permission from Fernhurst Books Limited.

Navigation: A Newcomer’s Guide is written by Sara Hopkinson. Sara Hopkinson is an experienced sailor, and a Yachtmaster Instructor and Examiner. She runs an RYA Training Centre at Pin Mill in Suffolk which specialises in navigation, radio, radar and first aid courses. She was a Coastguard Rescue Officer for many years and was the Station Officer of HM Coastguard, Holbrook.