Powerboat Manoeuvring In Wind & Current

Book Extract

Current

In order to effectively master boat control it is necessary to appreciate the power of the tide or current. On a day when there is little or no wind, move your boat out into open water, switch off the power and sit. Study the drift. The current movement will change over a period of time. If there is no wind the boat will drift with the current. With the engine now running and in forward gear, face the boat into the current. Ensure that the approaching current is passing the bow exactly equally along both sides. When in position, drop the gear lever into neutral and use the current as the brake. The boat will gently slow down and stop over the ground. Once the boat has stopped over the ground, the water will still pass the hull at the speed of the current. Left in this position the boat will eventually stop and start to slowly drift backwards.

Keep the bow facing the current and, as soon as you notice the boat starting to drift backwards, engage forward gear (but only on tick over) until the boat starts once more to move forwards. Move gears into neutral, and again the boat will slow down and stop. Without any use of reverse gear the boat will stand still over the ground. The quicker the current moves, the more the power is required to hold station over the ground.

Under power the lower drive leg or outboard engine leg acts as the rudder to direct the stern. Many say that the power has to be applied before you have steerage. This is not true as the lower leg offers a little steerage all the time water is streaming past the hull. But in order to keep the bow facing the current it is necessary to adjust the position of the lower leg. If the bow starts to drift to port (left), spin the top of the wheel to the right. The water passing the leg will move the back of the boat to the left, bringing the bow back to face the current. If the hull is allowed to drift at the same speed as the current, any spinning of the wheel will be lost. As soon as the bow moves off its heading by a few degrees, power will have to be used to bring the bow back into the current.

Wind

One can have the boat perfectly balanced against the current and then suddenly be pushed off course by an unseen gust of wind. Wind direction can be seen by the way the flags fly on stationary boats, the direction smoke drifts from a bonfire or chimney and the direction that birds take flight. (Large birds such as swans take off into the wind.)

A further and often better method of discovering wind direction is to look at the waves. Wind generated waves are usually at right angles to the direction of the wind. When the wind is approaching (looking to windward) the waves appear to have dark-coloured, sharp edges, whereas looking downwind (to leeward) the waves appear to have soft, sloping edges. Wind waves are generally at 90 degrees to the wind. This will accurately show wind direction, but what of strength and gusts? A gust of wind on the water can be seen as a dark patch moving fast across the surface.

Just watch the surface on a windy day and the pattern on the water will give early warning of an extra-heavy gust. Some of the dark areas will pass by without effect, whereas others will build quickly and very close, catching one off guard. With a very steady breeze the water will be of a uniform pattern.

Handling In Wind And Current

Never work to the wind alone. A flag will give you the wind direction but is not affected by the power of the current. When you are returning from a trip out, always come back in and drop into neutral. Watch carefully and decide on the direction of approach. Once you have found the position where the boat will stop, use this angle of approach to pick up your mooring or come alongside your jetty. When correctly balanced, you should not need to use reverse (unless you have chosen the stern approach).

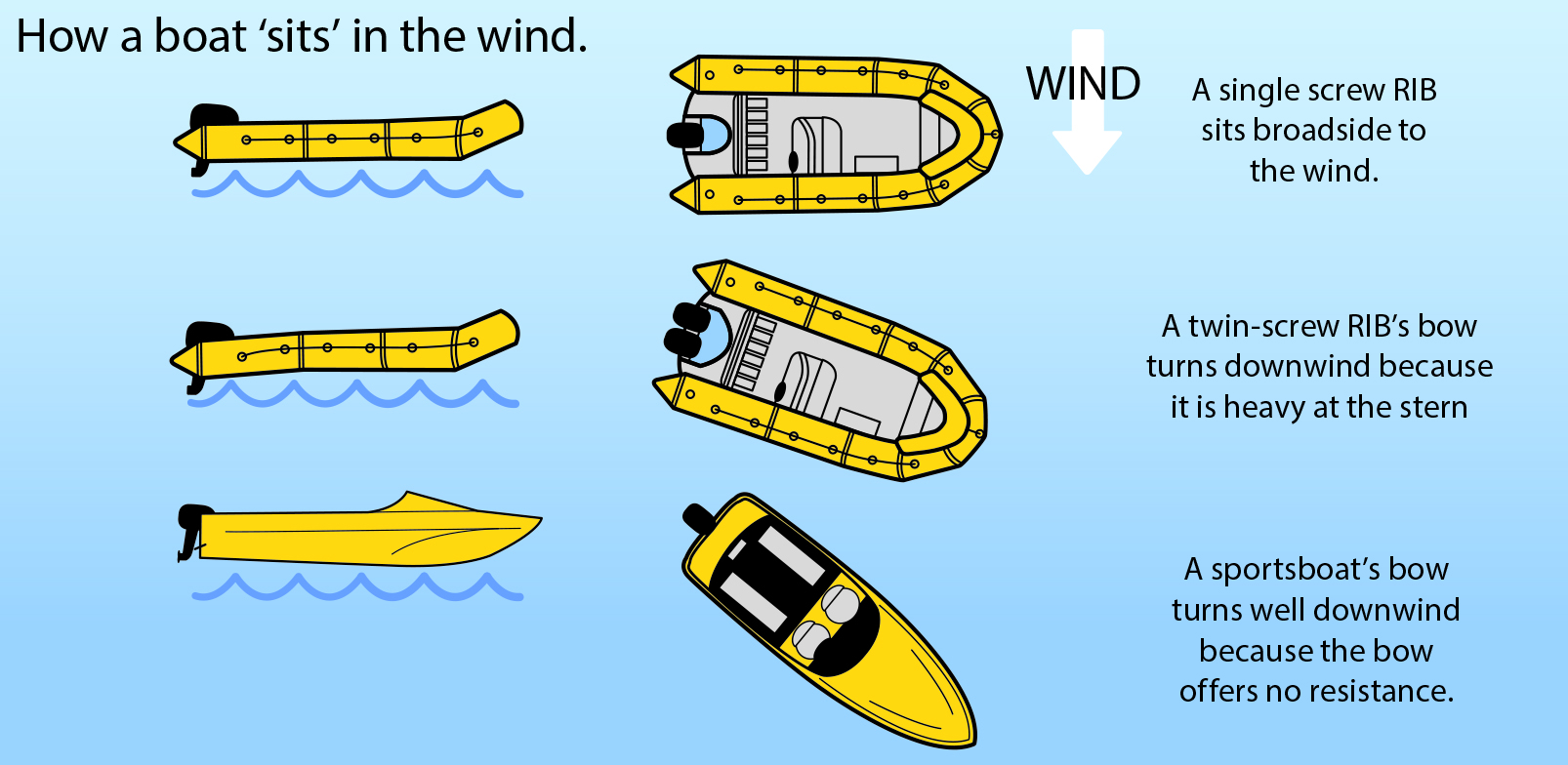

How a boat ‘sits’ in the wind.

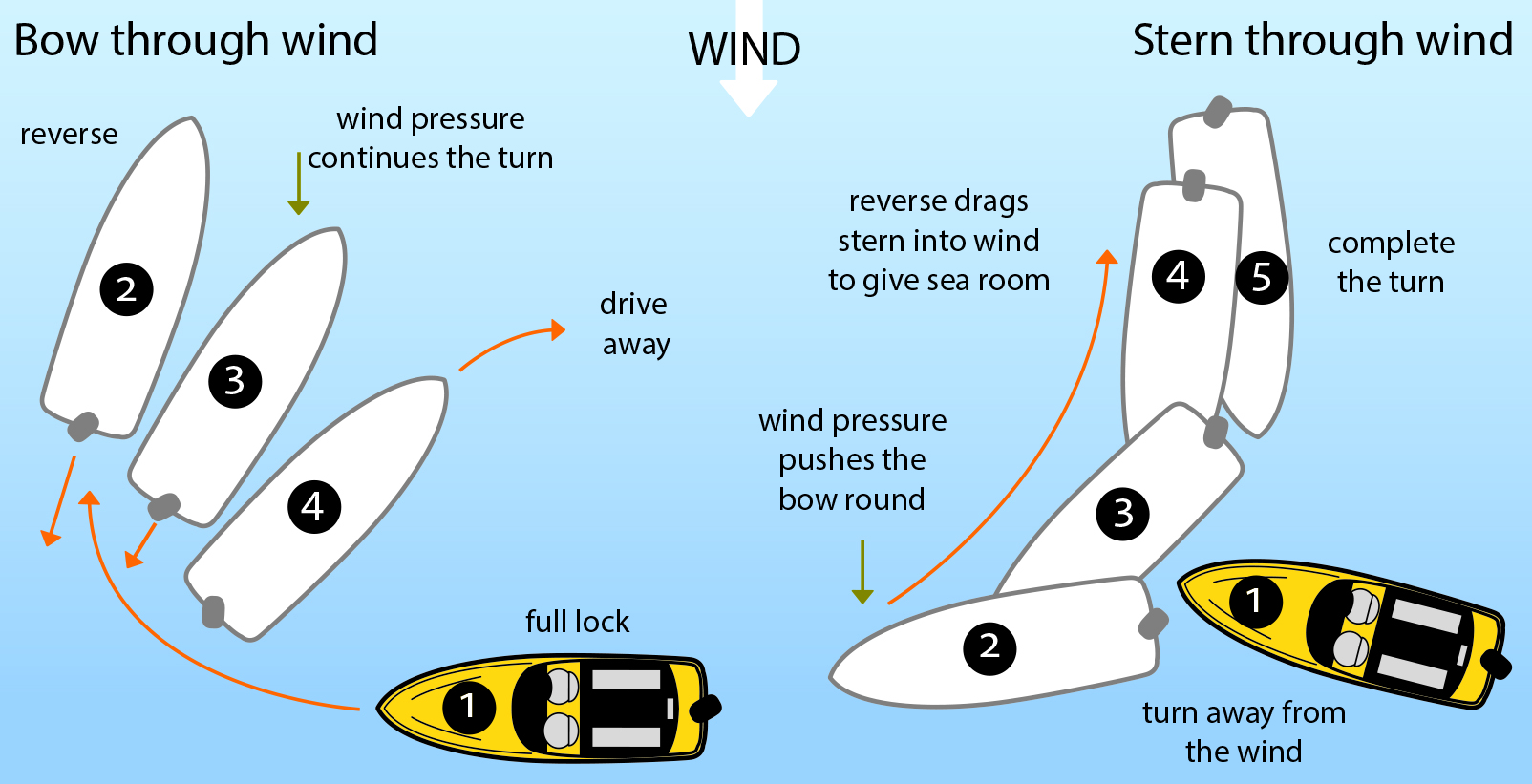

Bow through wind and Stern through wind

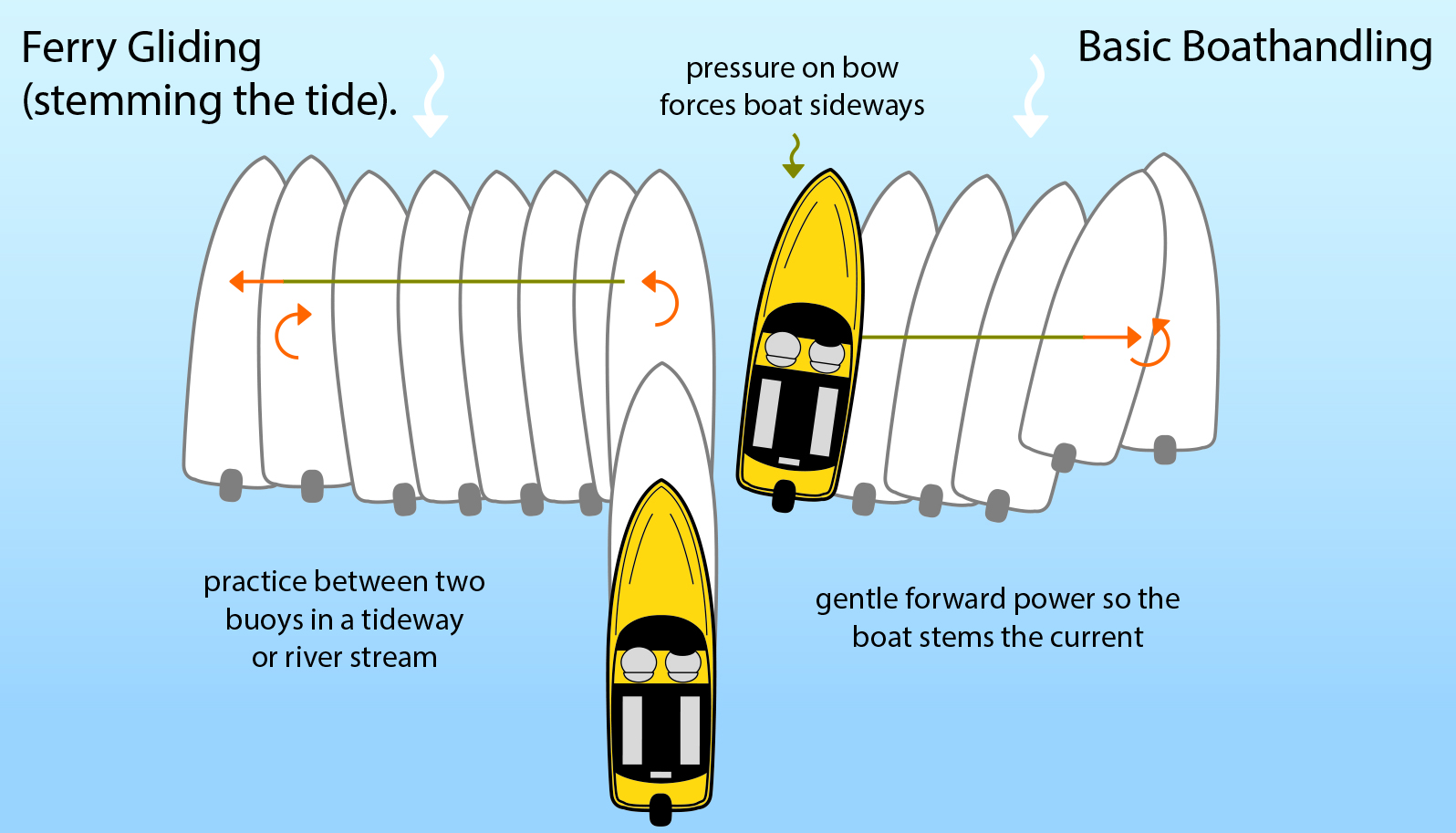

Ferry gliding

Ferry gliding, or stemming the tide, is an intricate part of boat manoeuvring at slow speeds.

Move your boat into the tidal stream/current and hold position. To find out if you are stationary you will need to look at other craft on moorings, jetties, the foreshore, trees and buildings and use these as transit marks. If you are fortunate to have a river or estuary in a quiet and empty backwater, it may be necessary to drop a couple of sinkers (floating buoys). Place them fairly close together across the current and use them as transits. Having mastered holding station over the ground, deliberately turn the top of the helm wheel in the direction you wish to go. The stern should start to respond in the current. As the bow turns slightly off the direct line of the current to around 10–15° to the helm, and as the boat starts to drift astern, just drop the lever into ahead tick over. The boat will now move across at the angle you have chosen. As soon as forward movement becomes apparent, drop the gears back into neutral. The boat will now be moving sideways.

As long as it does not go too much astern or ahead it will move sideways between two points.

This an important exercise for mooring against a jetty, as the current acts as the brake.

Once ferry gliding has been mastered going ahead, turn the boat around, offer the stern to the current and hold station. As the boat starts to swing in the current, move the top of the helm wheel in the direction that you wish to go in order to correct the drift. Usually the stern tick over gives sufficient power. Having engaged reverse there will be a short delay before the boat starts moving. Be patient. If you have the engine facing the correct direction, the hull will start to move back into a central position in line with the water current. A sideways stern approach to a jetty offers an amazingly high degree of accuracy. In some conditions, it is the only option available for a satisfactory docking.

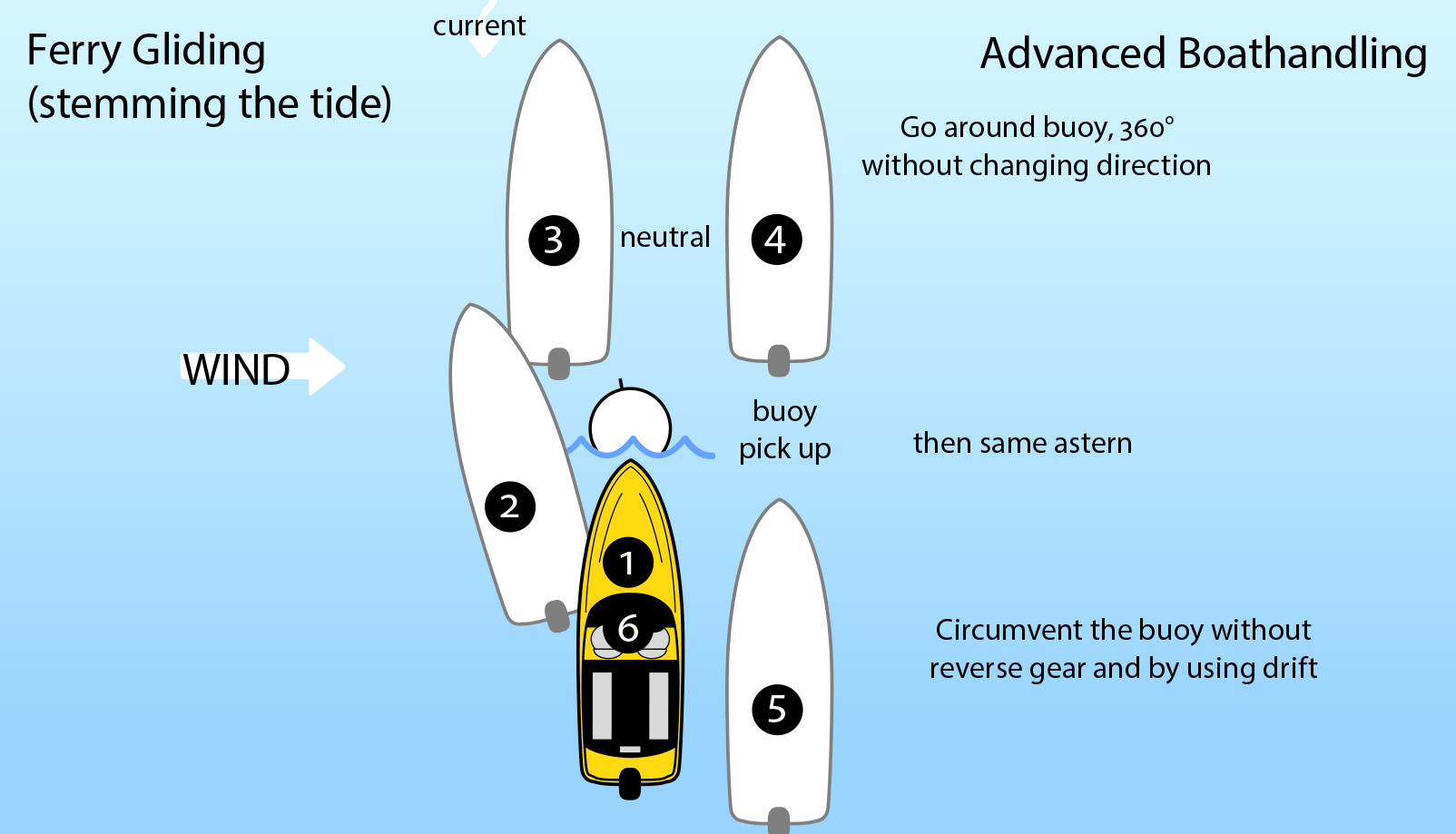

The principle explained

The boat stands still over the ground with the water streaming past both sides. As soon as the boat turns to port or starboard there is an increase of pressure down the side facing the current. This causes the boat to crab sideways into the low-pressure area created on the opposite side. Using this ferry glide principle, I was able to stand still under the bridges on the Thames each time a heavy shower came through. This kept me dry whilst others around me were getting very wet.

If there is sufficient current you could use the ferry glide principle to move sideways across the water to the mooring. A choice can also be made as to whether to pick up forwards or astern. If using the astern approach onto a mooring, always check that the mooring is clean – without floating lines etc. You can approach a swinging mooring from any direction. This is not the case with a jetty, which is fixed. When docking against a jetty, again check the direction of wind and current. Never assume that the boats already on the jetty are facing the correct way. They could have arrived some hours earlier when tide and wind were in a totally different direction.

Holding station over the ground and using the ferry glide technique is superb when you are approaching a busy jetty. If a boat is about to leave and is making space for you, just stand still over the ground and block anyone else’s approach to this space. This manoeuvre is no different to waiting for someone to leave a car parking space. If you were to drive off round the car park, it is likely that by the time you reached the spot again it would have been filled by another vehicle. A helm who does not understand the basic principles of holding a boat stationary in the wind and current will cruise around in a long circle only to find the space has been taken by others.

Ferry Gliding (Stemming the tide) – Basic Boathandling

Ferry Gliding (Stemming the tide) – Advanced Boathandling

© Not to be reproduced without written permission from Fernhurst Books Limited.

Powerboating: The RIB & Sportsboat Handbook is written by Peter White. Peter White has spent over 40 years on the water, of which the first 15 were teaching young people to sail dinghies and training RYA Instructors and Senior Instructors. He is now a professional powerboat trainer, the principal of Seafever International and leads Honda's powerboating training. Peter is a member of the Academy of Experts and an Associate Fellow of the Royal Institute of Navigation.