Start Lines & Windshifts

Book Extract

The start of the race will be the first test for your instrument system. You will have two main jobs to do; the first will be to work out which end of the line has the advantage, and secondly, which is the best tack out of the start line. For both of these tasks you will need to use the sailing wind direction. We will leave aside such concerns as general strategy for the course, be it tidal or wind, and any impact this might have on the end of the line or the first tack. The instruments cannot really be expected to help you with this, although we will see later that a computer system can.

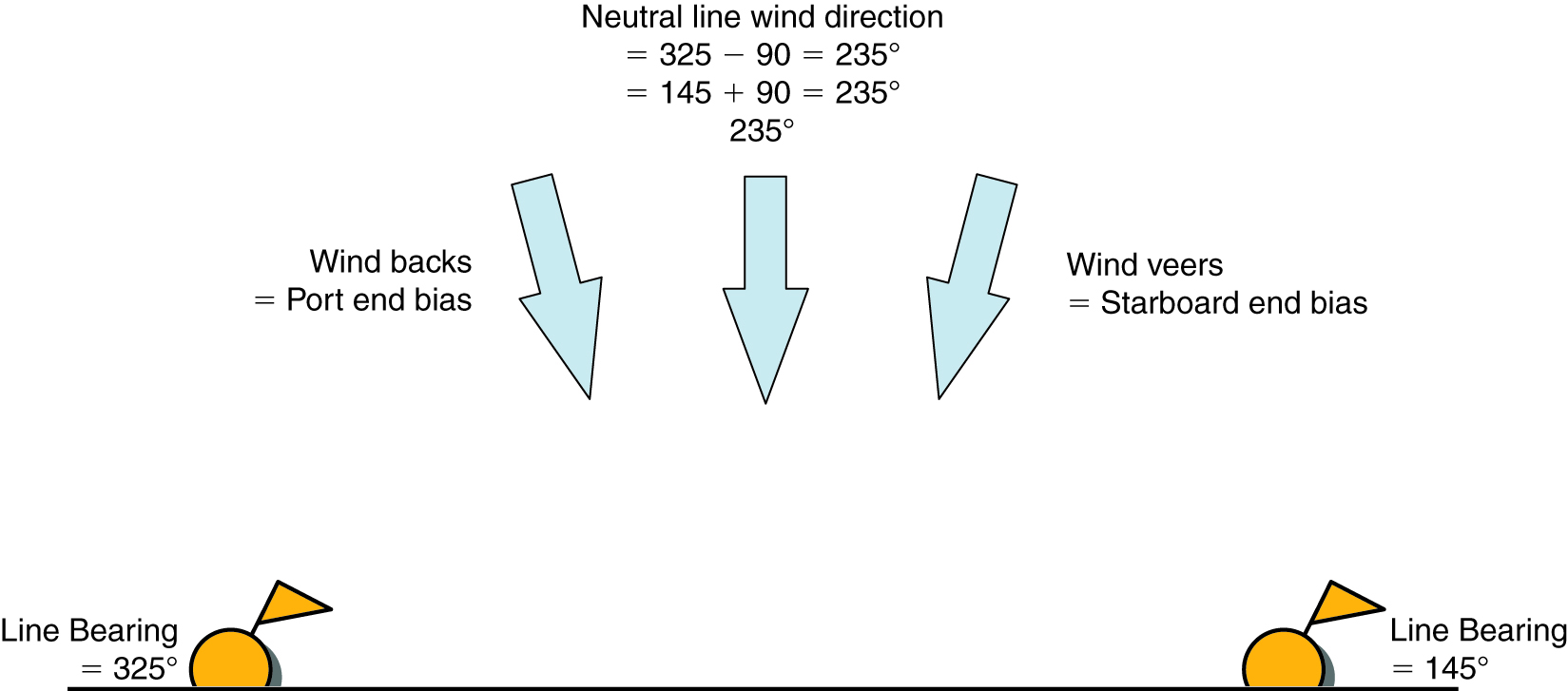

Choosing which end of the line to start from means choosing the one closest to the wind. The easiest way to work it out is to take a bearing along the line. Then add 90 degrees if you took the bearing from the starboard end, or subtract 90 degrees if the bearing is from the port end (Diagram 4.1 ). This gives you a value that I call the neutral line wind direction. It is the sailing wind direction that is completely square to the line, i.e. there is no advantage to starting at one end or the other. If the wind veers from this then the starboard end will be favoured, and if it backs the port end is favoured. Once you know the neutral wind direction all it takes is a glance at the sailing wind direction to tell you the favoured end.

Now you need to track the sailing wind direction down to start time. Using this information you can then pick the end of the line in time to get there for the gun.

Calculating the Neutral Line Wind Direction.

Remember that if the wind is oscillating you may need to anticipate the shift that you will be on at start time. Imagine a situation where at nine minutes to go the port end is biased; but by six minutes to go the wind has swung and the starboard end now gets the nod. With three minutes to go it is back to the port end – but if you made the decision to head that way you might well find that at the start gun the starboard end is favoured.

Tracking these shifts down to start time is more or less just a question of writing down the time and the number on the display. But we must keep in mind all we have said in the previous sections about calibration and damping. You must check the calibration of the sailing wind before you start taking wind readings. Calibration errors are often particularly severe when the boat is tacking from reach to reach – which tends to happen quite a lot before the start. Don ’t be fooled into thinking that there are huge shifts around when there are not. Damping is another problem when the boat is being thrown around in the starting area; particularly when it is combined with lots of dirty wind from all the sails and confused seas. In fact, when it comes down to it you will be hard pushed to get a decent reading when you get into the final approach to the line. So it is really important that you have a clear idea of what wind directions you are expecting to see once you clear the line.

The start is a time when you must try to divorce yourself from everyone else ’s immediate concern – which is getting a good start – and look ahead to the first couple of minutes of the beat. Your first job is to work out what the wind is doing as you come off the line. You have to know whether the instruments are settled on the number they are showing or just spinning past it as the damping tries to cope with some radical manoeuvre the boat has just executed. In short, you need to watch it all the time. It is never easy to ignore the excitement of a start, but you will look pretty average when, as soon as you are off the line, the tactician turns round and says, ‘Are we up or down?’ and you do not know.

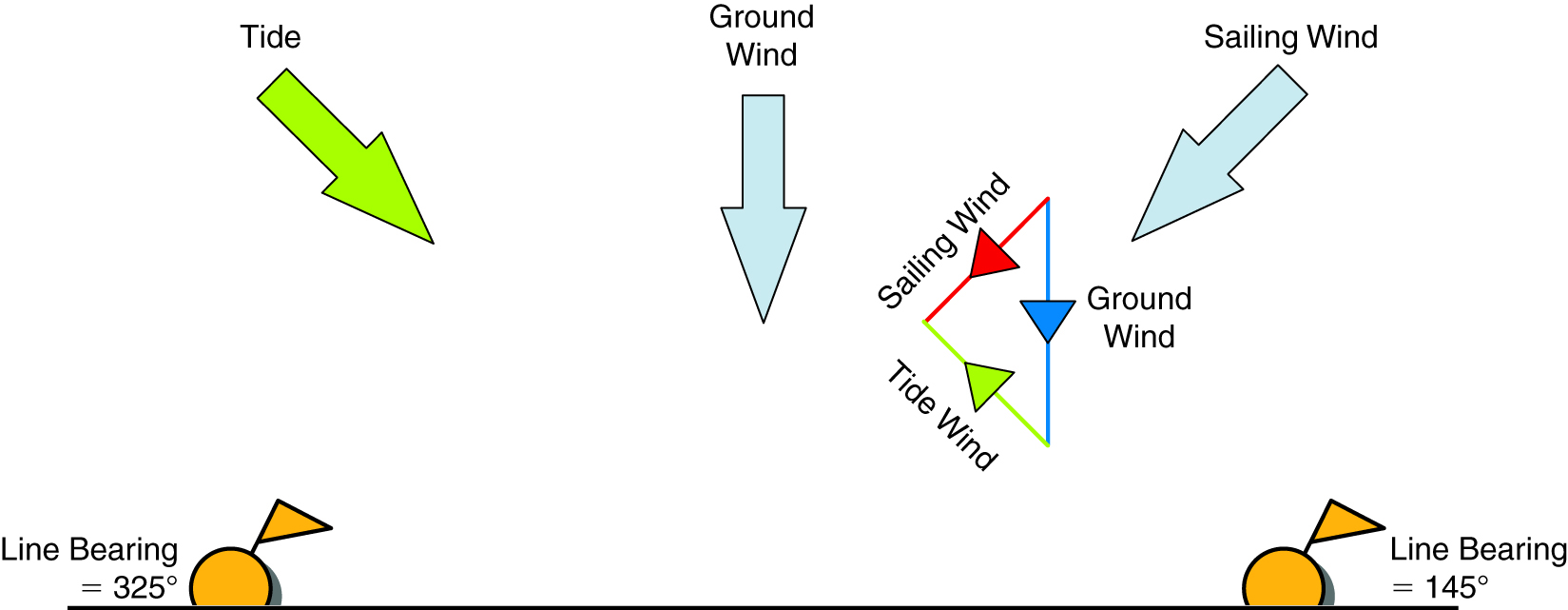

One complication you need not worry about is the effect of the tide on the start line wind. Sometimes an inexperienced race officer will set a badly biased line. The reason for this is that he is measuring the wind direction from a boat that is anchored to the seabed – and so it is the ground wind that he is recording. You are sailing in water that may be moving relative to the seabed and so your sailing wind will have a tide wind component (as we mentioned in the section on the wind triangle). This tide wind component can alter the wind you are sailing in quite dramatically (Diagram 4.2 ). If you ignore the tide and set the line to the ground wind you may well have a substantial bias. The good news is that your on-board instruments (assuming that you are not also anchored) will read the sailing wind that includes the tidal component. It is only the race officer, who is anchored, that must account for it in his calculations.

The line would be square to the ground wind, measured from the anchored committee boat, but has substantial starboard bias to the tidally altered sailing wind.

One final point about wind shift tracking. We had mentioned earlier that changes in wind gradient and sheer may affect the calibration of the sailing wind direction. This poses a problem; how are you supposed to recognise calibration that has altered whilst you are racing? If, for instance, it started altering when you tacked in a manner that your calibration did not account for, how would you know? Would you not just assume that the wind was shifting as you tacked? For a while you might, but after three or four times you ought to be suspicious. Three or four tacks on dud information could cost you the race, so here is a check you can use. Keep a note of your compass headings on each tack as a back-up. These will also tell you if you are headed or lifted. As soon as you are worried that the sailing wind direction is playing up you can check what it is telling you against the heading.

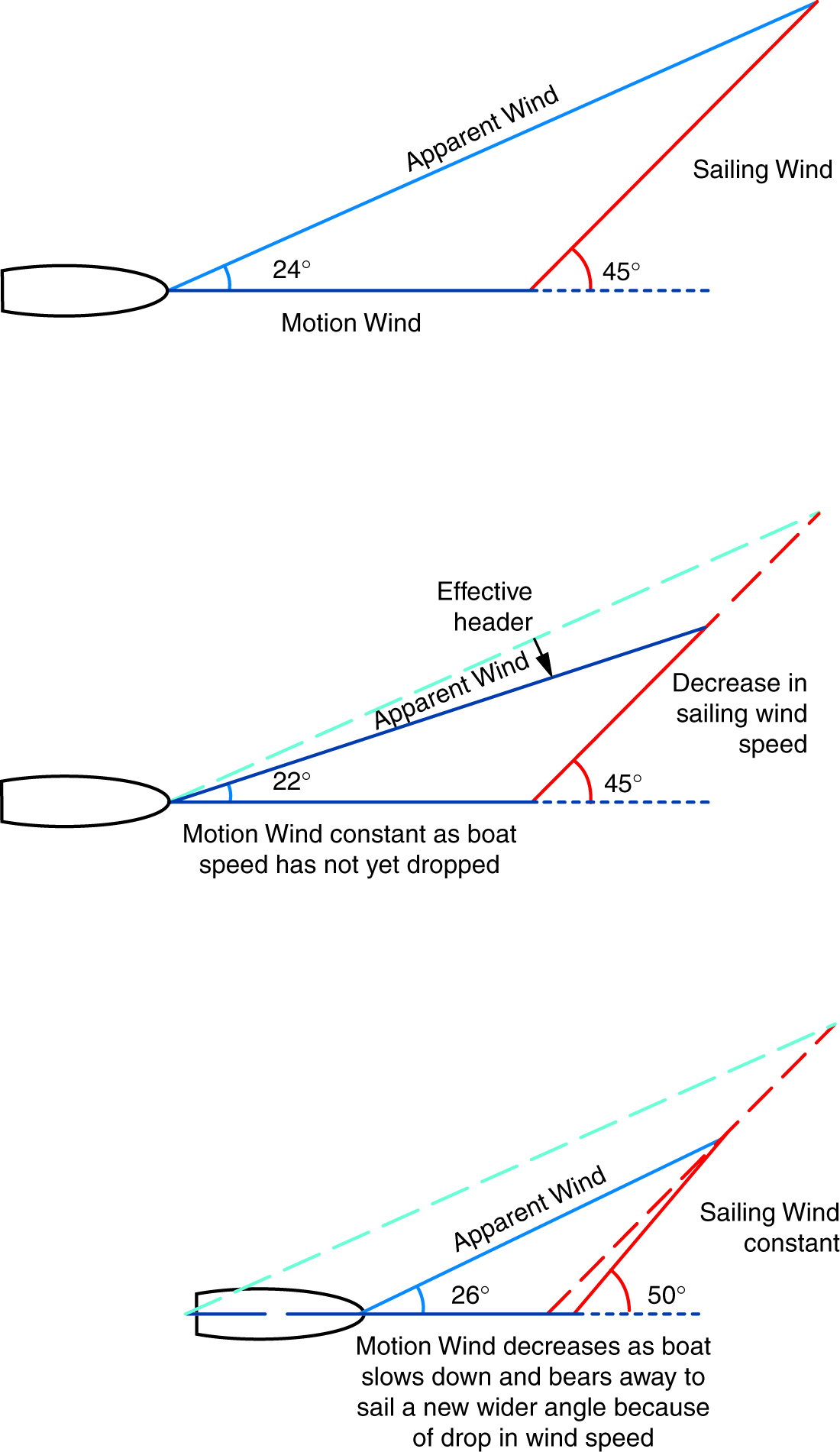

Unfortunately there is a problem with this as well, since the true wind angle a yacht sails at is dependent on the wind strength. The stronger the wind the closer you can sail to the wind, until about fifteen or twenty knots when the angle does not get any narrower and may even widen as the wind increases towards thirty knots. Your compass will often tell you that you are headed or lifted when in fact the wind direction is the same, but the wind velocity has altered. This is known as a velocity header or lift, and is accentuated by what happens to your apparent wind when the sailing wind first changes. Diagram 4.3 shows the case of a velocity header. As the wind drops, the boat has sufficient momentum to keep its speed for a few seconds, which moves the apparent wind forward, lifts the jib and gives the impression that you have been headed. It is important that the helmsman does not bear away too hard when this happens because as the boat slows down to match the new wind speed the jib will stop backing, and you can gain ground to windward by holding course and letting the speed drop until the jib refills. You will have to bear away a little because of the new wider true wind angle for the lower windspeed.

Do not be fooled into tacking by the velocity header, and it is equally as important to be careful when checking your sailing wind direction against the compass heading so that you do not start worrying about the sailing wind direction unnecessarily. The sailing wind will ignore velocity headers and lifts, whereas the compass will not. So you really have to keep an eye on them both, each to check the other. In the next section we will see how we can use the heel angle to help with a similar problem with the true wind speed.

The Velocity Header.

© Not to be reproduced without written permission from Fernhurst Books Limited.

Sail Smart is written by Mark Chisnell. Mark Chisnell divides his time between professional sailing and writing. He has competed as a navigator at the highest level and has written a series of technical sailing titles. Mark has also written three fictional titles.