Squalls

Book Extract

Squalls are self-contained convective systems, often confined to less than a mile or so in diameter, but they can occur in clusters of several hundred miles in spread. They are common in the Tropics, and the warmer the water is, the more active they will be. The first thing is to work out where they will move with respect to you, and during the day the Mark 1 eyeball is the best method to use. Simply treat any worrying squall cloud as if it was an approaching ship – if it is on a reasonably steady bearing and doesn’t seem to be going to port or starboard of you, then it will pass over you. Likewise, if it seems to be opening its bearing to pass ahead or astern of you then that is what it will do. At night a good radar watch should be kept, so make sure, if you have it, that you look at your set every quarter of an hour or so. A visual watch is still effective at night of course, as an approaching squall will start to block out the otherwise bright stars. If you do pick one up on radar, put an Electronic Bearing Line (EBL) on it and monitor it – if the squall marches straight down the line it is going to pass over you. At this point you may want to change course, reduce sail or both!

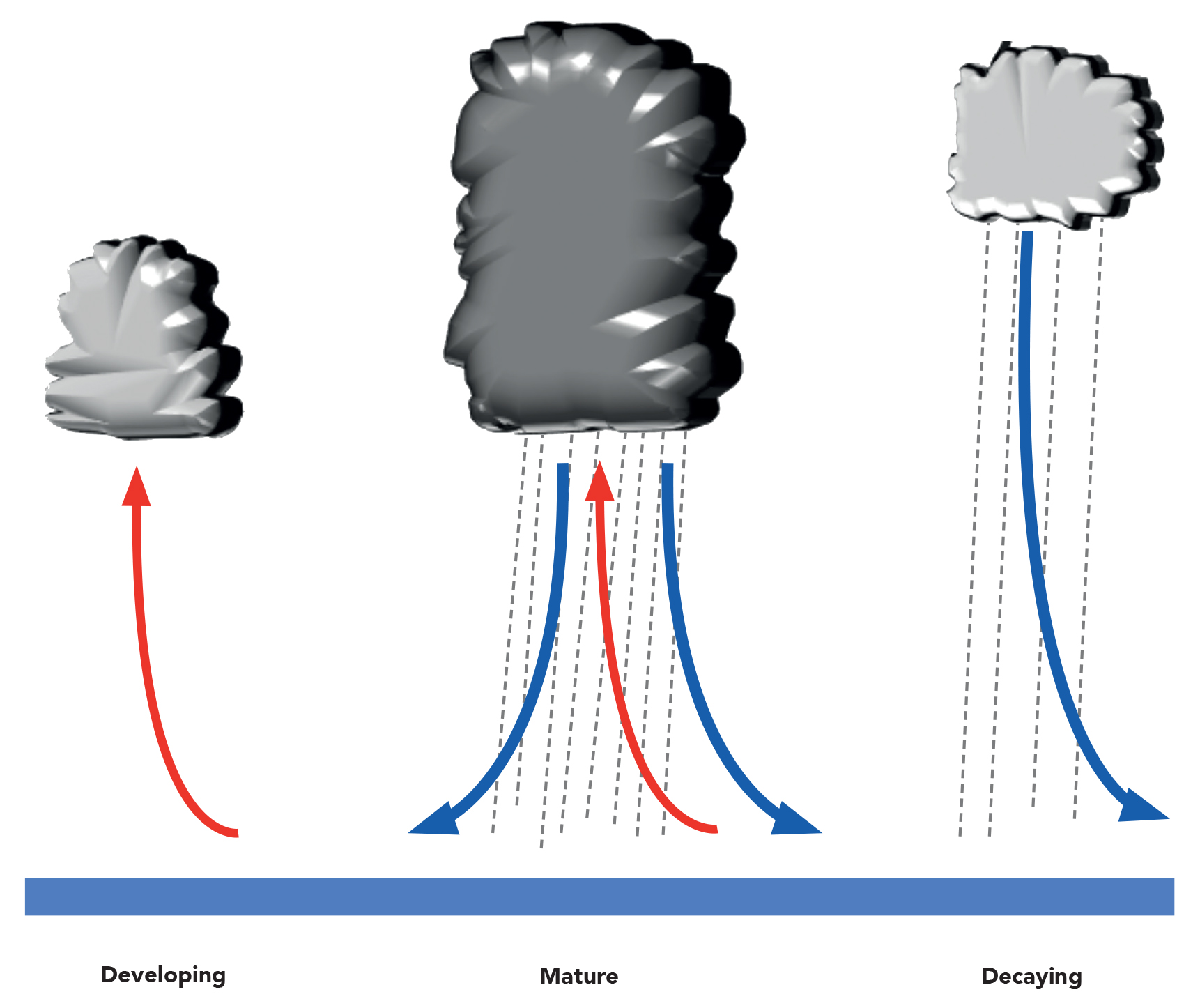

Let’s look at a simple squall first:

- Warm air will rise to start with and, as it is over the ocean, it will be moist.

- As this rises it cools, and the water will start to condense to form clouds.

- The cloud droplets will increase in size until their weight exceeds the upward force of the updraft and they will fall as rain.

- As the rising air reaches the top of the squall cloud it will have been cooled more than the surrounding air due to the energy taken out by the water condensing and so this air will fall down the outside of the cloud and some inside it as cold downdrafts (which is what you often feel just before a squall actually passes over you).

- Also, the raindrops themselves will drag air down with them, causing further downdrafts inside the cloud.

- This eventually counteracts the updraft of warm air, and the squall just seems to rain itself out, with the cloud base getting higher and higher until it disappears.

Squalls developing at dawn in the tropical Northern Atlantic

The development and self-immolation of a simple squall

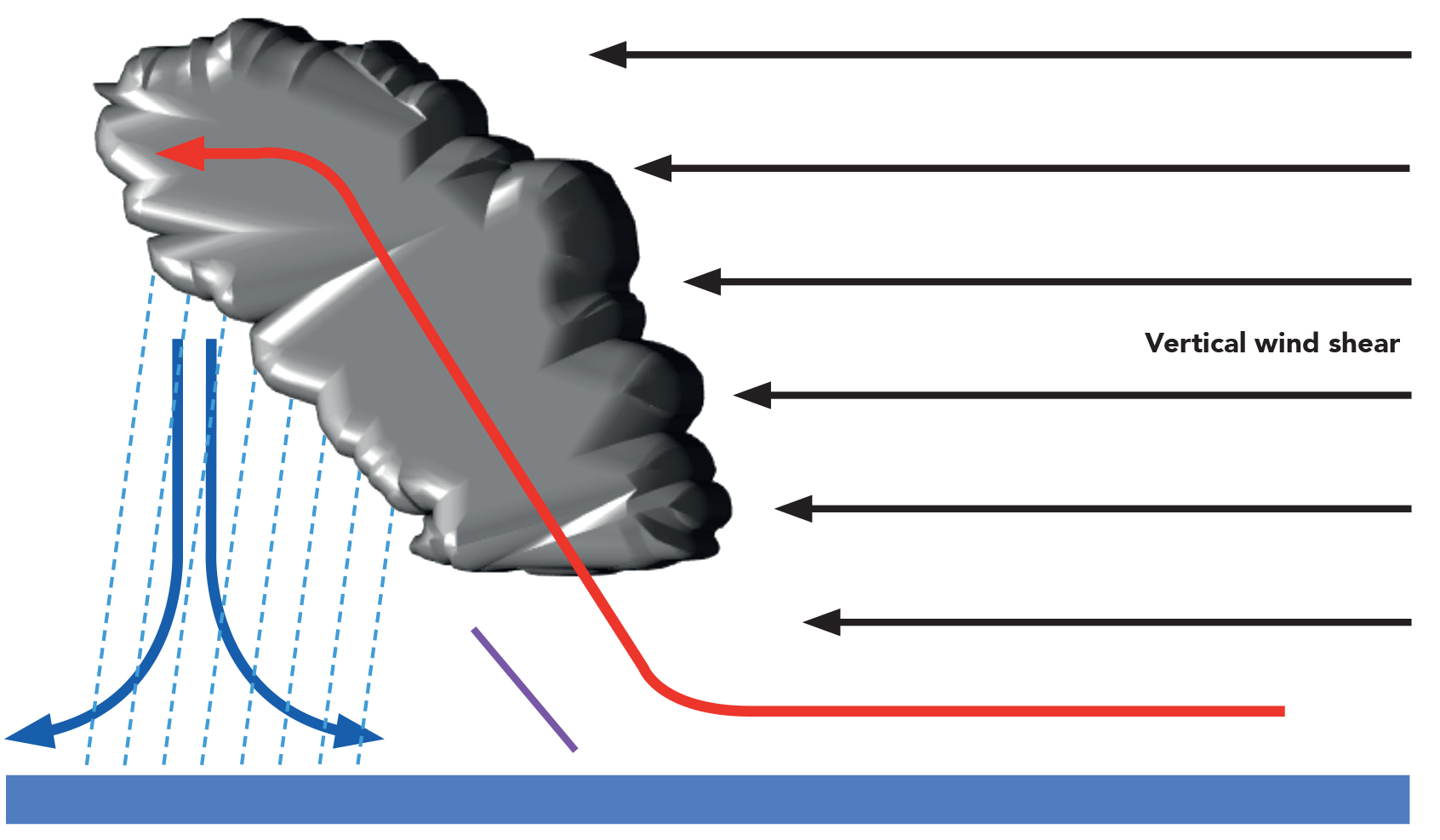

However, if there is a steady wind blowing this will give wind shear, the phenomenon whereby surface friction slows the surface wind down and it increases in speed with altitude until the steady gradient wind speed is reached. This is the situation which will give rise to self-sustaining squalls:

- The wind shear makes the whole convective system lean over, which then makes the precipitation and therefore the cold downdrafts fall away from the warm thermal updrafts.

- As these cold downdrafts hit the surface, they spread out in all directions, including against the regional wind.

- As the cold downdrafts are denser than the surface air they will actually force this warmer air to rise (shown by the diagonal purple line in diagram overleaf) and this process will carry on at night like a miniature front – the system is effectively generating its own lifting mechanism.

- Also, if the velocity of the downdraft as it spreads out over the surface is the same as that of the regional wind, the system will effectively stay at the same place – and if that’s directly above your boat, you have no choice but to bob around until it slowly moves off

A self-sustaining squall

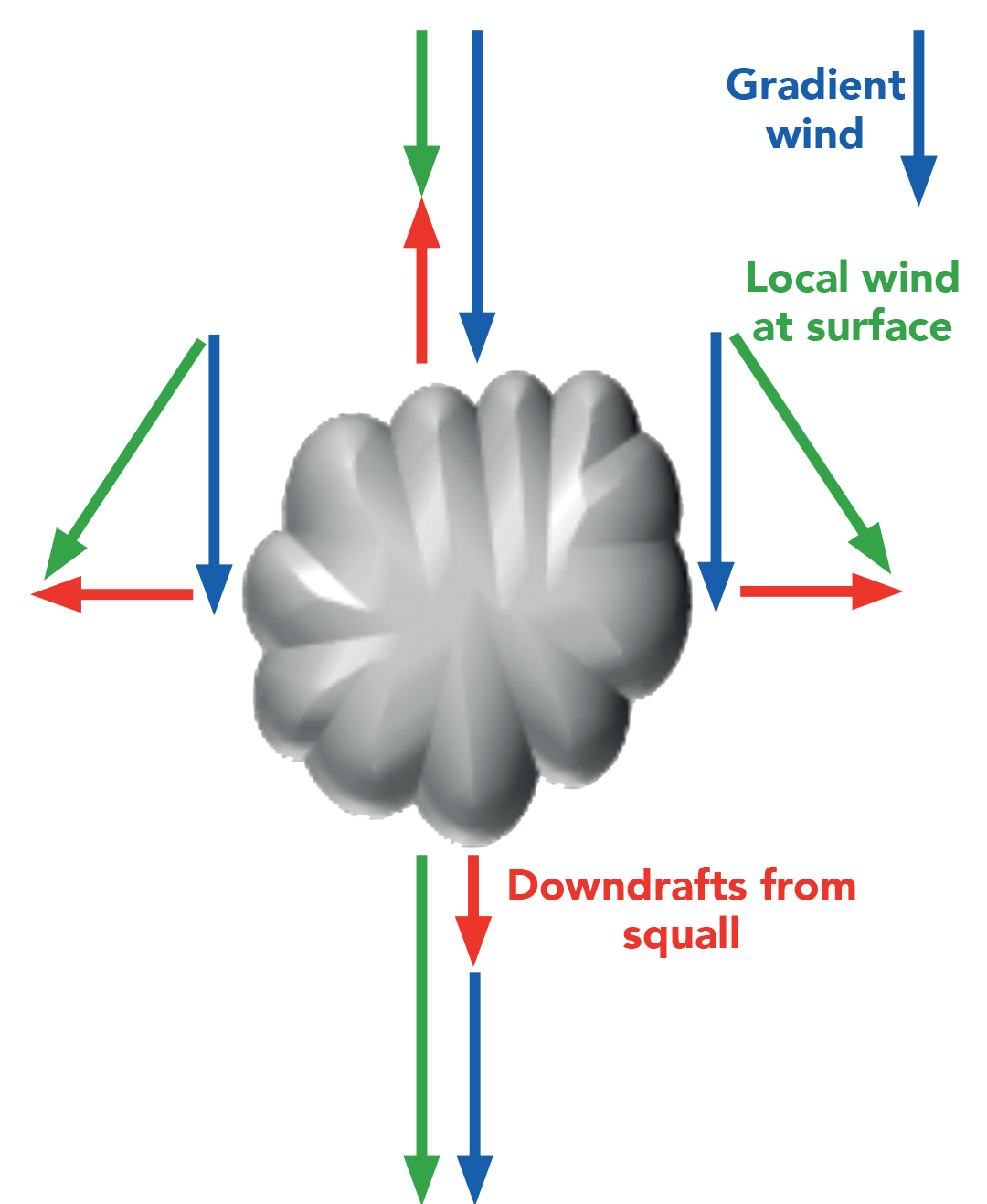

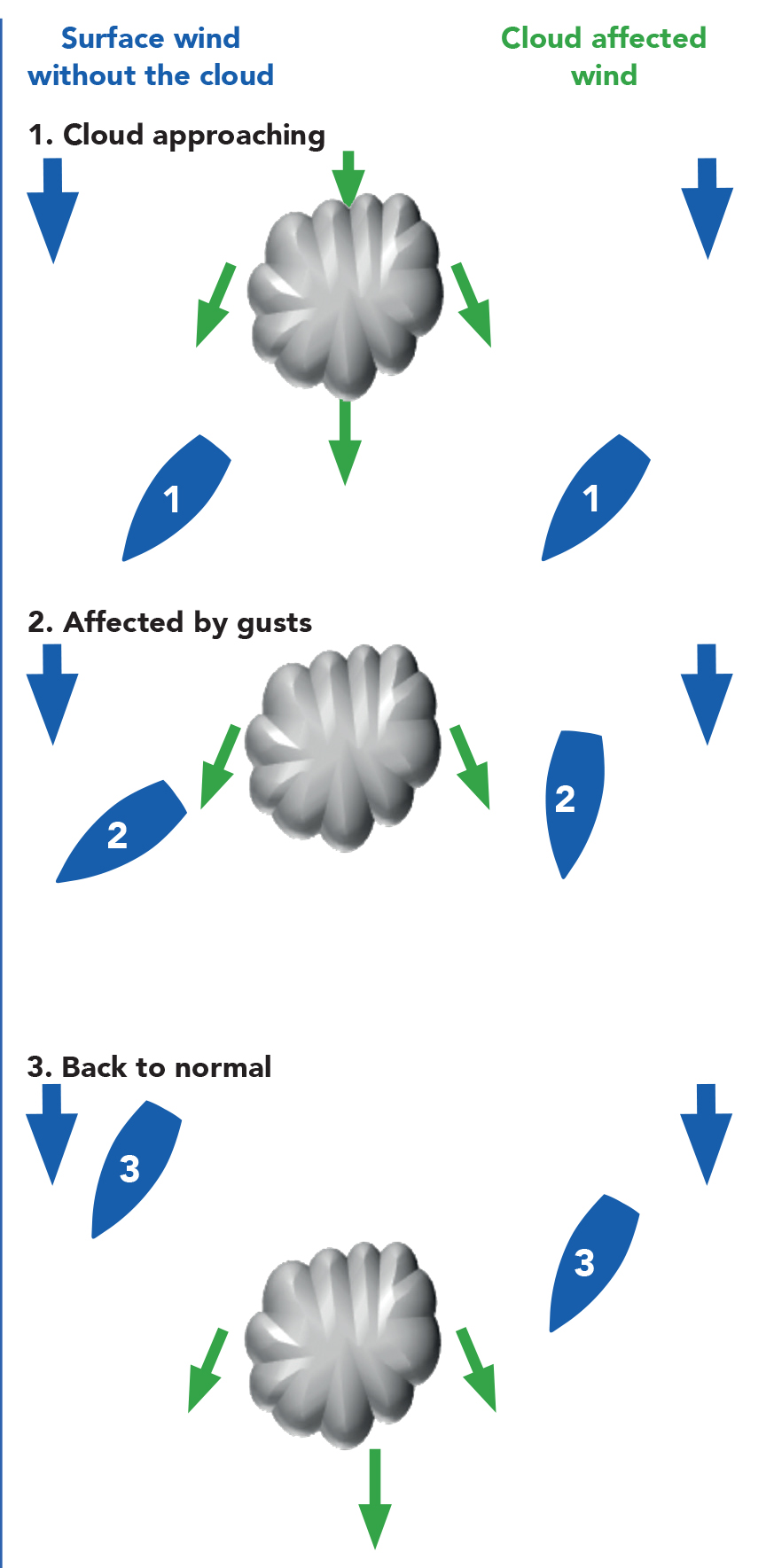

The squall will also have a localised effect on the general gradient wind:

- If the squall is directly coming at you, the gusts will add to the gradient wind, increasing the wind you feel.

- If it passes ahead of you, the gusts will act against the gradient wind, decreasing or sometimes even reversing it.

- If the squall passes to the side of you then, depending on the spatial relationship, it will back or veer the wind – basically the local wind always blows away from the base of the cloud.

The effect of squall gusts on local wind

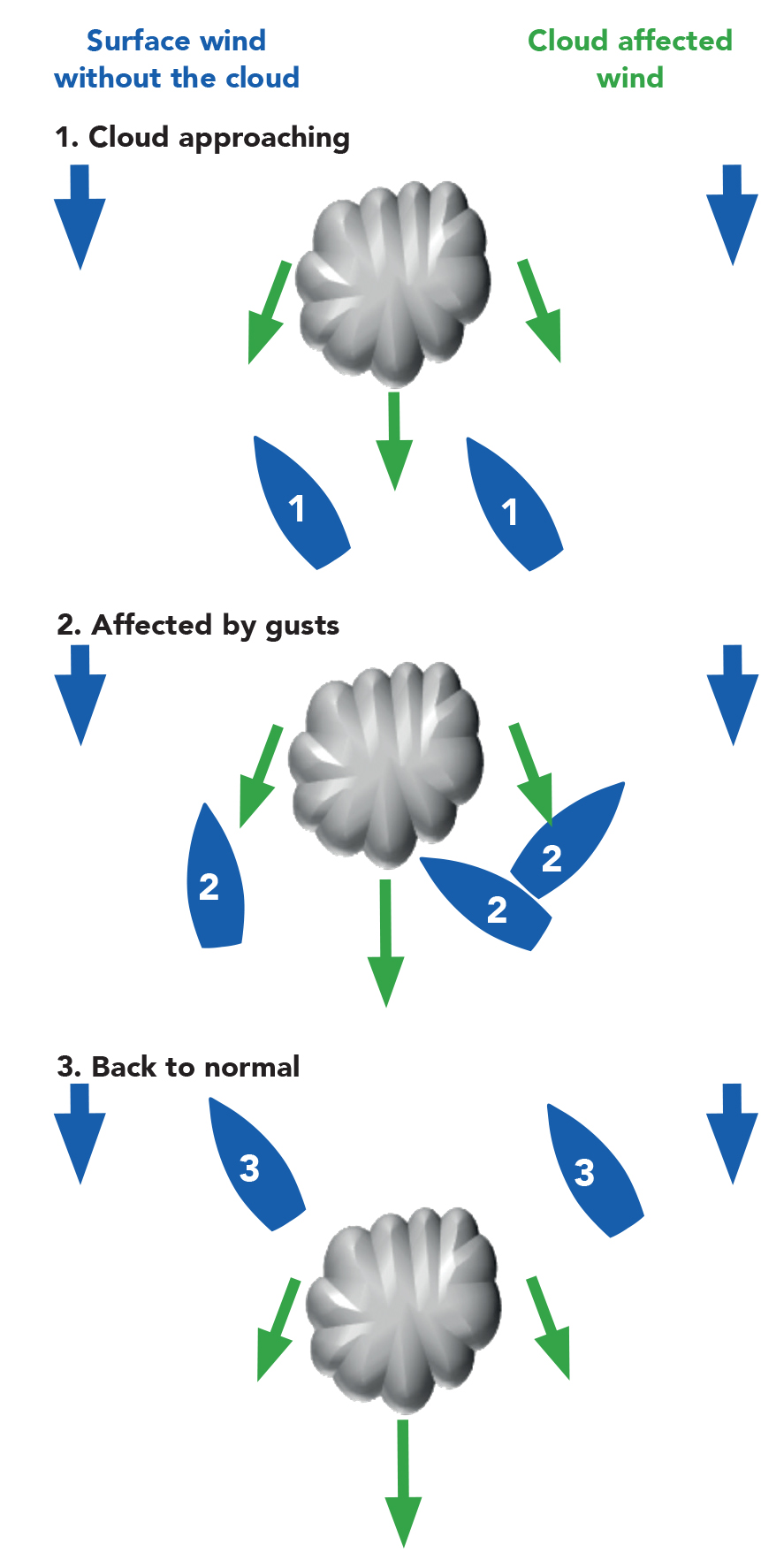

If you’re sailing upwind and a squall comes towards you then it all depends whether the squall is going over, behind (your windward side) or ahead (down your leeward side) of you:

- If it passes behind you then you should get lifted, with stronger wind, until the squall is past.

- If it goes ahead of you then you’ll be headed as it approaches, so you can tack and take the lift on the opposite tack before tacking back again when you’re subsequently headed as the wind reverts to normal.

- If it goes overhead, then hang on to the mainsheet and enjoy the gust!

While going downwind, if the cloud comes on your windward side, then you end up being lifted as it goes past, while if it passes down the leeward side you’ll be headed.

A squall while going upwind

A squall while going downwind

© Not to be reproduced without written permission from Fernhurst Books Limited.

Weather At Sea is written by Simon Rowell. Simon Rowell is a world-class weather forecaster and yachting professional. He has skippered a yacht to victory in the Clipper Round the World Race and has been forecaster for that race since 2011. Since 2015 he has been the meteorologist for the British Olympic Sailing Team.