The Modern Diesel Engine

Book Extract

Compared with its forbears, the modern diesel is light in weight and relatively high revving. It is in all ways comparable to the modern petrol engine but more economical to run and a little more expensive to buy.

Modern diesels range from around 10 horsepower right up to 1,000 or so in the leisure and commercial engine ranges, for under 24m vessels. Some of the newer larger engines do have electronic control and / or management systems, but the vast majority of small diesels are purely mechanical, apart from the starter motor and sometimes a fuel solenoid.

The type of engine we use should be dictated by the use to which it will be put.

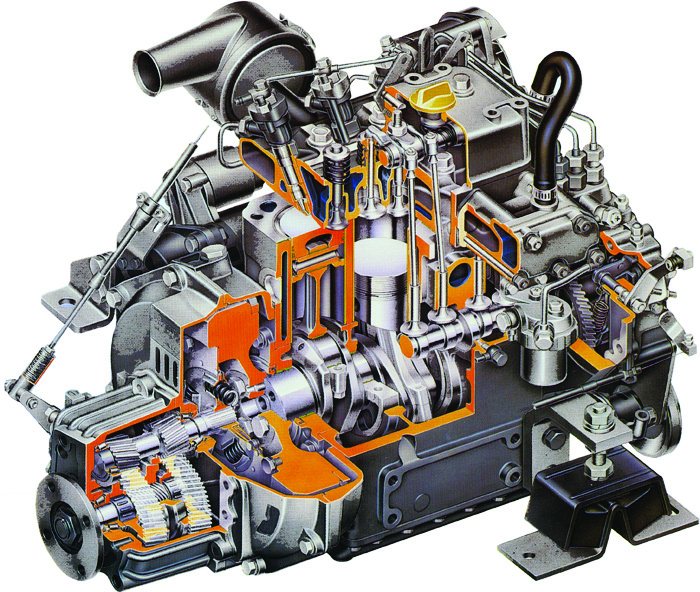

Cutaway drawing of a small modern diesel engine and its gearbox

Modern Yanmar diesel engine

Displacement Hulls

Where the boat’s speed is limited by its waterline length, relatively low power is required. The old rule of thumb was 2hp per ton displacement. Much more realistic in these days of needing to get home to go to work would be 4hp per ton. Many builders seem to be offering as much as 6hp per ton or even more, but this brings with it problems of high fuel consumption and engines that are run at far too low a power for normal cruising. Diesels need to be worked hard, so it’s no good saying that I won’t use all that extra power that I’ve installed ‘just in case’. If you don’t work them hard you are storing up problems for later, and sometimes sooner, in their life.

Displacement motorboats are normally cruised at a constant speed and the engine is in use all the time. The engine gets warmed up properly and, as long as it doesn’t have too many hp per ton, it gets a reasonably easy life.

A sailing boat’s engine has a much harder time, as often it doesn’t reach normal running temperature before it’s stopped. It’s also often used at relatively low power when ‘motor sailing’. These conditions are not good for a diesel, and even less good if it’s turbo-charged. Unless there’s just no suitable non-turbo engine of the power required, we’d suggest avoiding a turbo-charged engine in a sailing yacht.

A modern 36-foot yacht weighing 6 tons needs 24hp by the 4hp per ton rule. This would give a cruising speed of 6.6 knots with a fuel consumption of 11.5mpg. Install a 40hp engine, as many builders do, and you get a 7.3-knot cruising speed and 7.3mpg. Cruise that 40hp engine at 6.6 knots and you are using only 12.5hp, under a third of its rated power rather than the minimum recommended 50% (that’s power, not rpm). The argument about having extra power for heavy weather has a serious hole in it. If you bear away about 20 to 30 degrees from the direction of the waves, you’ll go faster, use less fuel and have a much more comfortable ride!

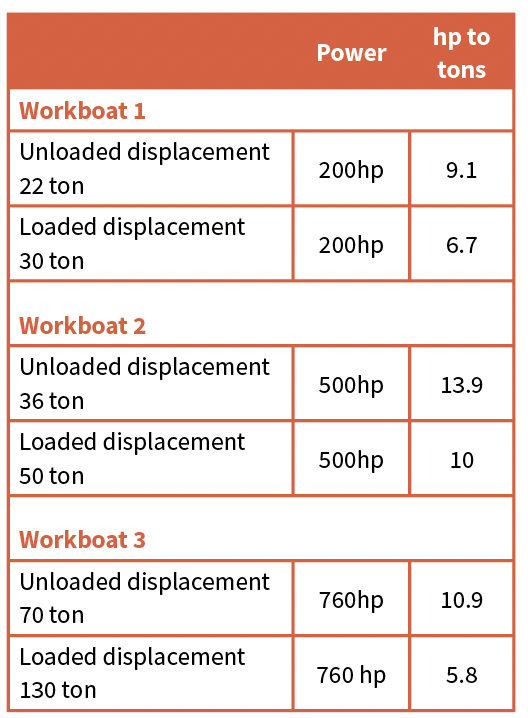

While all of the above is true for a pleasure yacht, workboats and fishing vessels do tend to have more power. For example, this table shows information from three different workboats, for the hp per ton:

It is interesting to see how much this ratio changes when fully loaded. Workboat 1 and workboat 2 boat have a PTO (power take off) for deck hydraulics such as capstans and a crane. While workboat 3 has an auxiliary for this, so all power is used to drive the vessel. Some workboats and a lot of fishing vessels have to tow, so this means a lot of power. The propeller for a workboat that tows is very different from a fast motor cruiser. A bit like a race car and a tractor, both can have the same power, but use it completely differently.

Semi-Displacement & Planing Hulls

These hulls need much more power than a displacement hull. Because of the demands that the engine should be as light and compact as possible, these engines are normally turbo-charged and can have electronic engine management. To save carrying redundant weight, these engines are normally cruised at about 300rpm below maximum continuous rpm. Heavy weather will require a reduction of speed, so you don’t need any extra power.

Hull design and desired cruising speed affects the power requirement and it’s not easy to use any rule of thumb, as it is for a displacement hull. Once the hull gets beyond ‘displacement speed’ you’ll almost certainly be using enough power to avoid problems caused by running a diesel at too low a power. If you are forced to slow to displacement speed and you’ve got two engines, shut one down if safe to do so.

These hulls are used for pleasure craft and fast workboats. These workboats don’t tend to carry much cargo, but often up to a maximum of 15 people.

Taken from Diesels Afloat by Callum Smedley & Pat Manley.

© Not to be reproduced without written permission from Fernhurst Books Limited.