Packrafting In Scotland

Book Extract

It was a bank holiday weekend in Scotland and the West Highland Line from Glasgow to Mallaig was packed out, but only one person got off the train at Morar station. There was nothing here other than a few houses, a B&B and a lovely sandy beach facing the isles of Rhum and Eigg. The waters of Loch Morar spill out onto those sands and meander down to the sea. Me, I was heading the other way, inland alongside the loch’s 20-km long north shore on a back road that turned into a track and finally a narrow path rising above the waters.

I was of course taking a very keen interest in the state of those waters. As must be normal around here, the wind off the North Atlantic was blowing up the loch with me, but not enough to make hauling the 20-kilo backpack on soft rafting shoes any easier. It looked like a downpour had recently smothered the area; transient waterfalls were running down the valley sides and occasional squalls rushed up the glen.

By the time I got past Swordlands Lodge – a WWII-era spy training base for the predecessors of MI5 – all I wanted was a flat patch of dry land to pitch. I’d got further than I thought, covering about 14kms in 4 hours and was now just 7kms direct from the bothy (refuge) at the far end of the loch. The wind had calmed, but the bothy could wait till the morning. I spread out on a narrow jetty, inflated the boat and went for a walk over to Tarbert Bay, a few houses on the tidal Loch Nevis where a ferry drops in from Mallaig every other day on a circuit serving the otherwise inaccessible community on the Knoydart peninsula. The paddle up Loch Morar and short portage over to Loch Nevis to follow the coast back to Mallaig was a popular day trip for sea kayakers.

Never mind about that. The thought of my first real, fully loaded packrafting paddle alone on the 1000-foot deep Loch Morar was a little unnerving. Even freshwater inland lochs like this are prone to sudden storms that have drowned ill-prepared canoeists. How would my boat handle in a swell with a 12-kilo pack strapped to its bow?

When the time came next morning, I found I just went through the motions, knowing that I’d done my best to get it right. Sealed inside a dry suit, I pushed off and tried to keep a respectful distance from the steep shore, as the bay I’d sheltered in overnight opened out into the winds. Out there, funnelled in by the 1,000-foot ridges, whitecaps furled the foot-high swell, but despite my dry mouth and hyperactive paddling, there was really nothing much to worry about other than worrying too much. With an open deck and the wind to my back, the loaded raft sat on the water as reassuringly as a wet mattress.

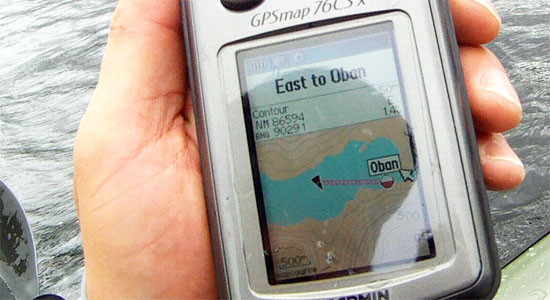

At one point the sun came out and soon after the white speck of Oban bothy came into view at the base of the narrow, cloud-filled valley which would lead me over to the next loch. Coming back to shore I felt a small sense of achievement; I’d managed seven whole kilometres across a windy loch carrying all my needs. With the wind and hard paddling, it had taken only one and a half hours, much faster than following the shore on foot, but that was enough adventure for one day. Though it would put me behind schedule, I decided to spend the rest of the day in the bothy, drying out the tent soaked by overnight rain and my dry suit soaked by over-anxious paddling.

On the map only intermittent paths lead to Oban bothy which seems rarely visited and is pretty basic but a very welcome shelter set in a brilliant location. Across the loch abandoned crofts reminded me that that this part of Scotland was not always the wilderness we like to think, but a land abandoned two centuries ago when poverty and inland expulsions to enable sheep rearing forced the inhabitants to the coasts, cities or overseas. Amazingly, in the next bothy the logbook showed a recent visit by some Canadians whose forbears had abandoned Glen Pean in 1793. With the gear drying on the line, I went for a walk up the valley to confirm just how mushy the track would be. Later that evening I scooted off in the empty raft across the loch just because I could.

Over The Pass

Next day was going to be a short haul, just 8km by GPS, up the valley and down the other side to another bothy in Glen Pean. I’d rather taken to bothy life. Though these places are basic and grubby, with no facilities other than a fireplace, some bed bases, left-over food and rubbish, the simple presence of space, shelter and mouse-eaten furniture is so much better than sodden tent camping.

While a packraft does open out your mobility options, especially in the Scottish Highlands, it does increase a typical 12kg camping payload by 50% once you add in a dry suit. Carrying that sort of load over the boggy, hummock-ridden terrain, where the high summer grass and reeds obscure knee-deep ditches and peat channels is probably more dangerous than bobbing around in the middle of a windy loch. To this end I’d adapted a sawn-off piece of paddle shaft to slot on the end on my AquaBound paddle to make a packstaff – something I’m still using over a decade later. It proved to be one of my best ideas on this trip, useful as a probe for boggy-looking ground that was often actually firm (and vice versa) and a balancing- or weight-bearing aid. Climbing or descending, it helps take the load off the knees and saved a lot of the energy expended in avoiding or trying to hop over peaty trenches which could suck you in down to your knees. I’ve been using the packstaff for packrafting and Scottish hill walks ever since.

With an improved packing set-up, I set off for the pass, no longer skirting the puddles and putting my weight onto the packstaff when needed. Taking it slow, I felt much safer with the staff as I plodded steadily up to the watershed. Here, still surrounded by boggy steep valley sides, a faint sheep trail descended steeply to a water-logged valley where it disappeared altogether. Even with a staff and wet-proof feet, the valley still took some negotiating, inching around outcrops while leaning on the firmly planted staff which would have pretzeled a Leki walking pole. In the end, it was simpler to follow the stony riverbed.

Presently I came upon Lochan Sagairt as marked on the map, unreached by paths from either side and jammed in among dense contours in a gorge. Either side would be a tiring climb with the load I carried and so here was a perfect evocation of the Packrafter’s Choice: to expend effort but possibly save time by keeping on land – or to deploy the raft and scoot across the lochan effortlessly and maybe even catch a bit of a ride off the stream on the far side.

It took just 12 minutes from stopping to paddling out through the reeds onto the lochan. Following the stream gave me up to a kilometre of paddling distance, but soon that became too shallow and worse still, up ahead seemed to drop through a small gorge. Very keen to play it safe, I rolled up the boat and took to what was now a quad bike track which brought me through a jungle of ferns to the deserted bothy in Glen Pean, nine kilometres walk and four hours from Oban.

Glen Pean

The plan here had been to track the Pean river on foot and put-in as soon as it became paddleable, hoping that that would lead smoothly into Loch Arkaig, the next big body of water. I had my doubts it would be as simple as that, and after lunch set off, first up to an interesting-looking waterfall on the far side of the valley, and then back down into the valley to recce the river downstream. This exposed one of the flaws of packrafting in this sort of wild terrain. Walking the water courses in the valley bottoms, you’re in the worst, waterlogged terrain, fit only for birds and slugs trapped in a squelching morass of saturated peat and spongy moss.

Up here the meandering Pean river flipped between deep, Guinness-coloured pools and clear, shingly shallows. No big problem in an unloaded raft as I’d found in France where we’d spent the last few months, but with a load you ground out sooner, meaning getting out and pulling or even unpacking and carrying; not an efficient use of energy. I tramped downstream around the deepest mire where the forest plantation met the river, and up ahead noticed an ominous dip in the tree line between two knolls. Deadly, Alpacka-shredding rapids!

A perfectly walkable track led through the forest to the head of Loch Arklaig and a group of houses known as Stathan. I looked closely at the 1:50k map and sure enough, where a path came down the valley to bridge the river and join the forest track to Strathan, two 25-metre contours crossed the river within a quarter kilometre.

To confirm that paddling the Pean may be more effort than it was worth, at 6pm I set off along the forest track to that bridge and suss out the river. An hour later I looked down on a two-metre drop before it led into a boulder-chocked funnel. My hunch had been right, though of course, terrified as I am of being swept unwittingly into a mini-Niagara, I’d have surely heard the waterfall and done something about it.

Back at the bothy, I was satisfied with my recce. The upper Pean was navigable with a little effort for about 4kms from the bothy to the bridge, but at the bridge you’d need to pack up and haul up a messy track into the forest and walk on down to Strathan, or stagger along the banks until the river cleared up. (I’ve since returned and paddled the Pean from that bridge down to Loch Arkaig.)

Loch Arkaig to Gairlochy

Next morning I stood on a bridge in Strathan, a few buildings of the Glendessary estate at the west end of Loch Arkaig. Below me the Glendessary river rushed towards the Pean in a tumble of white water, while the Pean river itself wound placidly into Loch Arkaig.

Like Morar, Loch Arkaig ran for 19kms end to end, a long paddle that might take most of the day and certainly most of the day’s energy. A back wind was rushing along, maybe only a little worse than on Morar; here would be a good place to experiment using an umbrella as a sail. A narrow road also trailed the loch’s north bank and having lost a bit of time hanging out in the bothies, I thought I’d try and hitch a lift towards the Great Glen and Loch Lochy where the Lochy River lead south to Fort William. If I could get there tonight, I’d have caught up with a chance to carry on to Rannoch as planned.

Plodding along the road eyeing up the loch, I passed a bunch of young canoeists on a course and figured if I couldn’t get a ride I’d be better off getting on the water and riding the swell down to the east end. Before that decision became necessary, a car squeezing past saw my thumb his mirror and half an hour later dropped me at the loch’s east end. Rich worked for the local Outward Bounds kids’ camps and spent his spare time adventuring himself on the islands and highlands. He told of some canoeists last winter who’d portaged the way I’d come yesterday. One ended up breaking her leg somewhere near Lochan Sagairt and getting helicoptered out. Portaging a canoe from Loch Morar? Have these people not heard of packrafts?!

Either way, I was sure glad I didn’t have to trudge down that long, loch-side road; I’m sure whitecaps or not, eventually I’d have taken to the water. Rich dropped me off somewhere near Clunes, a shop-less wooded hamlet surrounded by retirement homes. I was back in tourist lands on the Great Glen Way footpath. Possibly as a result of yesterday’s efforts, I suddenly became ravenous and tore into my food bag to boil up a mug of soup and some stew-in-a-bag paste while the wind howled through the trees. The freeze-dried food I’d been eating was pretty tasty and very easy to prepare, but for once, I wasn’t eating enough. Twenty kilometres away, Fort William would see to that.

All that remained to see was whether Lochy loch was paddleable in all this wind. Sure enough, the west bank was sat in a wind shadow. With a swell running at a couple of inches, this was a loch I could do business with. No need for the drysuit, just zip on the skirt to keep the insides try.

How nice it was to paddle on a calm loch. Back in phone range, I called the g-friend to fill her in on my triumphant achievement. A lighthouse marked the top lock on the canal: right for the canal and Gairlochy, left for a weir which led down to the river. Camping by the lock on trimmed grass was free, and many recreational boaters were berthing for the night. Fort William and a seafood basket with salad, chips and a cappuccino would have to wait. I pitched the tent, de-aired the raft, and went to suss out the state of the Lochy River from the towpath.

Between the trees and the wild raspberry bushes I spotted some fly fishermen by a couple of sporty rapids and found a good place to put-in tomorrow just past the lock. I was getting a bit desperate for proper food, but Gairlochy had nothing except all-you-can-eat wild raspberries. The nearest resto was up towards Spean Bridge, more than my blistering feet could manage.

River Lochy to Fort William: Riding the Wavy Trains

I was fairly sure I had the measure of the River Lochy, a canoeable river that led down to Fort William and tidal waters, interrupted only by one Grade 3 rapid which the Scottish canoe guide warned of but didn’t locate. A look on Google Earth had pinned down the probable location where the river took a hard left with a telltale smudge of white. I put it in my GPS.

I set off down the Lochy, knowing I’d be having a lunch of real food off a plate, not out of a bag. It was great to be riding the wavy trains again, with nothing above WW1 as long as you chose the right chute. At one point I hit 14.5kph (9mph) according to the Garmin and safe in my drysuit, what control I had steered me from tedious shallows or boat-flipping boulders. The grade-three waypoint was right on the money, where some young boys where being tutored in the art of fly fishing by a ghillie (river gamekeeper) dressed in full regalia, including a deer-stalker hat and a crimson face.

Inspecting the rapid, I’d have been curious to see how even a proper kayaker could manage to fly down the chute and stay upright where it ramped up to the left to flip you right, straight onto the rock. UK Rivers rates the Lochy quite lowly and barely mentions this rapid, but then goes on to add that a poacher and no less than a dozen commandos have drowned here over the years. The mossy, muddy portage was another job for the packstaff, and now a little braver, I took the hardest lines through the remains of the rapids and presently rocked up at the rail bridge at Inverlochy, a suburb of Fort William.

Loch Ossian

It was Wednesday lunchtime and my train out of Rannoch was due in 48 hours. If I was to make it, I’d have to move on that afternoon, but after checking into a hostel I was dizzy with hunger. The afternoon would have to be spent answering the call of the stomach. In between I paid my respects to the outdoor gear shops in search of bargains, but merely confirmed the daunting truth: other than a couple more dried meals and some 2-for-1 mini karabiners, there was nothing I needed.

The next day the train dropped me off at lonely Corrour station, a mile away from the lovely wind-powered SYHA hostel alongside Loch Ossian. All that remained was to spend the afternoon paddling down with the wind to the Corrour estate lodge at the far end of the loch and walking back along the shore to satiate another ravenous appetite.

I now have an idea about packrafting in Scotland: what sort of routes are optimal and what gear works best. The recce around Glen Pean made me realise that no matter how up for it you might be, hiking cross-country across bogs and tussocks as I’d planned to do from Glen Nevis over to Blackwater and from there to Loch Laidon, would have been a hiding to nowhere while hauling a heavy pack.

If I’d had the time I’d have followed the West Highland Way out of Fort William to Kinlochleven and on to the Kings House hotel in Glencoe (40kms – two days). From there an eastbound moor path passes close to Loch Laidon (we did it years later, below); either can be taken to reach Rannoch station.

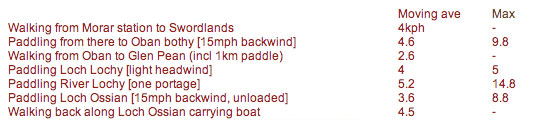

Speeds

The raft can be pretty quick on a loch, paddling hard with a backwind, even with a load, and so some sort of sail would reduce the effort and so give more range. I never expected to try and paddle the full length of Morar or Arkaig (19+ kms).

Loch Ossian (6kms long) was surprisingly slow as at one point I headed across the width of the loch with a stiff sidewind to see how the unloaded boat handled (pretty flappy but probably more secure than an IK).

By Chris Scott, author of Packrafting: A Beginner’s Guide

Originally published on his website