The Greatest Killer In Nelson’s Navy - Quirky History

Book Extract

1.5 million still die of it worldwide

No, neither cannon balls nor scurvy were the main killers. Dr Quirky continues his lectures on the history of medical science. If it hadn’t been for being self-isolating after Covid, he thinks he would have been in the UK lecturing the editorial board of The Lancet.

Nelson’s Victory from my school book

In the previous chapter about Dr Ted, the local GP from Berkeley, we touched on the disease that claimed his wife and 21-year-old son: consumption, as it was called then, tuberculosis or TB as it is known today. A crippling lung disease which neither alpine air nor long sea voyages could cure. With the tolls from smallpox and TB that scythed through Europe 200 years ago, it amazes me there were enough left to lose 50 million to the so-called Spanish Flu and still overrun the planet with seven billion of us.

It is generally accepted that seamen in Nelson’s Navy stood a better chance of a healthier life than the nine million who were in Britain at the time, trying to keep the place going and providing enough export income to fund the war. Apart from the monotony, the Navy diet was generally considered better than the landman’s at the time, chomping a whopping 5,000 calories a day. Two pounds of beef on Tuesday and Saturday and one pound of pork on Sunday and Thursday. It certainly had a higher proportion of meat than most of the population.

And it came with free booze. Originally this had been a gallon of beer. Yes, eight pints a day. I couldn’t have managed that over a long weekend even in my prime. But it was safer to drink than the ship’s water. But even beer went off in the tropics and was replaced by half a pint of spirits. Because Britain had sugar plantations in the West Indies, the industrial waste became rum. And it was cheap. That’s why it became the Navy’s choice tipple. This was watered down 1:4 in the 1740s but even so, most of the sailors spent their lives half pissed. The Lords of the Admiralty continued this until 1970 when they thought that if you would fail a breathalyser test after the 11:00am tot and couldn’t drive a car, you really shouldn’t be driving a submarine.

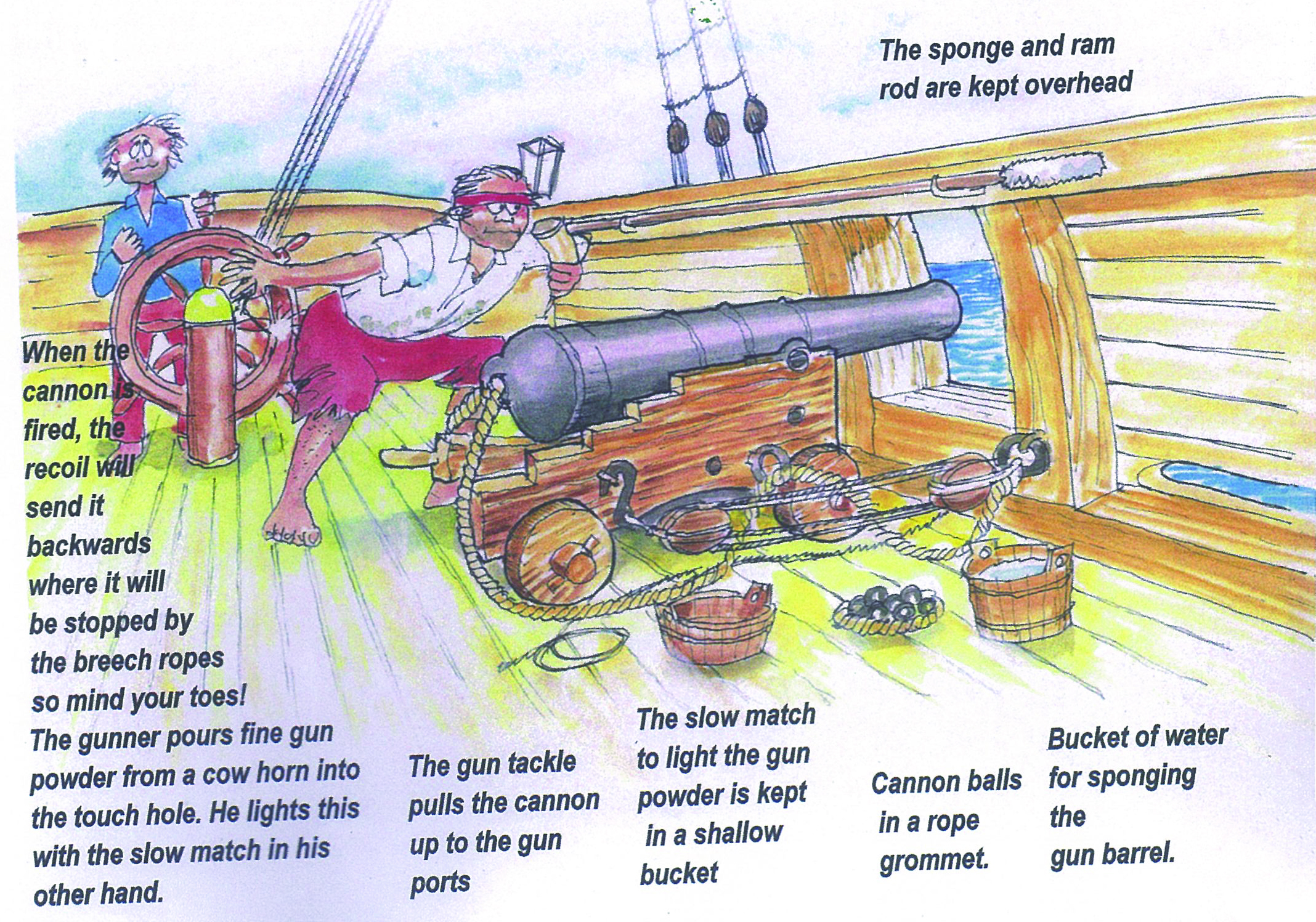

This illustration is from a book I wrote for my grandchildren The Pirates of Patonga, where they are captured but engineer their own escape and shows how a cannon works

The fastest knife in the OR

If you were going to have a limb amputated without anaesthetic in the 19th century, you would want it to be over as soon as possible, and then Dr Robert Liston was your man. He had a sort of production line going and perfected his speed in amputation to minimise shock to the patient and to cover as great a workload among the suffering as he could in a working day. Despite this, he had a low fatality rate of 1-in-10 when 1-in-4 was the going rate. The Guinness Book of Records was not around to record his personal best of two and a half minutes, including sewing up, when he amputated a patient’s leg and the fingers of the assistant who was holding him down. While rapidly changing knives, he accidently caught a spectator’s coat who thought he had been stabbed and promptly died from a heart attack. The patient and assistant later succumbed to infection. This 300% casualty rate from one op obviously detracted from his overall batting average. He became the first surgeon in the UK to use ether as an anaesthetic. Good for the patients but maybe not for the staff and spectators when the operating theatres were lit by gas lamps... Boom!

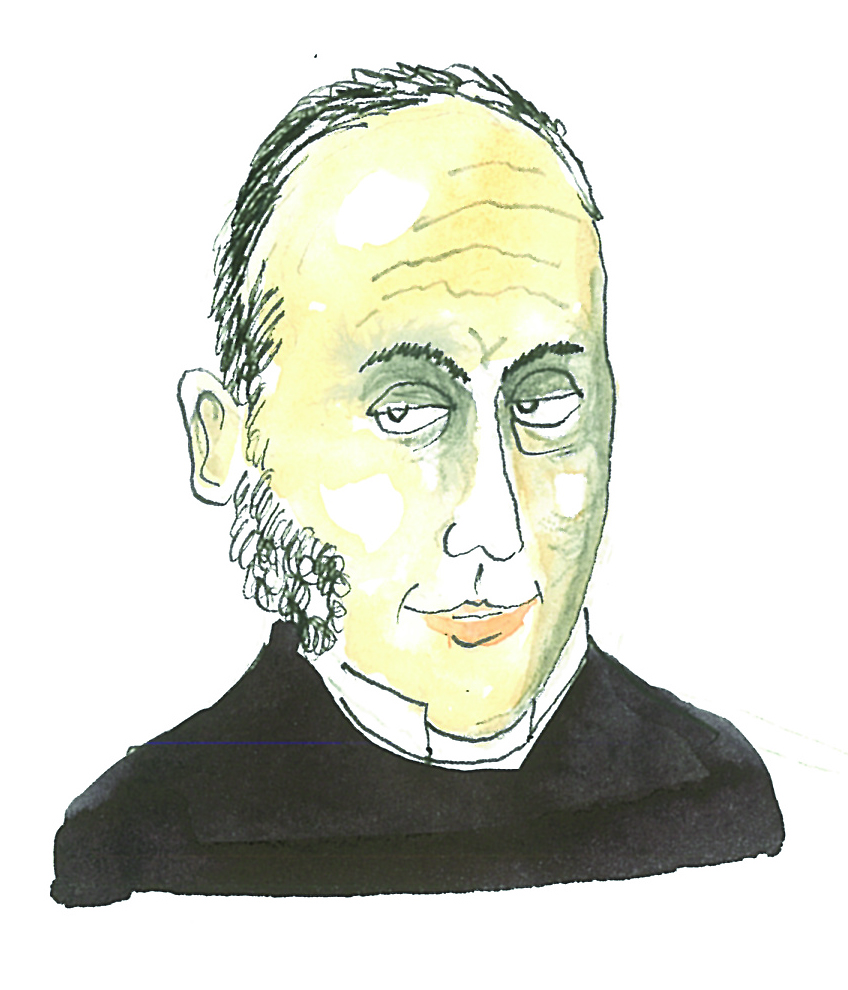

The world’s fastest amputator, Dr Robert Liston, from a portrait by Samuel John Stump (I don’t make this stuff up!)

While smallpox vaccinations were compulsory in Napoleon’s army, it was voluntary in the Royal Navy and many declined ‘for religious reasons’. Scurvy had been partly brought under control after Navy doctor James Lind’s successful experiments using lemons on his patients. The Navy only took 42 years to accept it in 1795 and it was only at the urging of other naval doctors who had read Lind’s work.

Captain Cook you will remember had similar success with sauerkraut and malt. I remember enjoying the malt to take away the taste of the cod liver oil we war-time kids were given, together with sun lamp exposure to replace sunlight to give us vitamin D. I think sunshine was on ration then too.

The antiscorbutic power of lemons was reduced by storage and boiling, which was used as method used to make juice. Plantations were set up in the West Indies to grow limes. Because they were more acidic it was wrongly thought they were the better fruit. In fact, limes have only 29.1mg of Vitamin C per 100 grams versus 53 for lemons. See? Homework doesn’t stop when you leave school.

OK, so they had smallpox and scurvy sort of under control, apart from yellow fever, what’s next? How about cannon balls? Actually no. Despite Britain having over 150 ships of the line and being at war with France and just about everybody else for over two decades, very few of her sailors saw more than one sea battle despite what we read in Forrester and O’Brien where they seem to occur every few pages.

The French naval museum in Paris claims loads of victorious French naval victories that did not appear in my history books. But then, that museum had never heard of Trafalgar.

The Royal Navy’s ships spent most of their time on patrol, bottling up the French and Spanish Fleets so they could not leave port and actually get into combat. Nelson famously said, “Harbours rot ships and men” meaning that their lack of sea-going practice with ship handling and gunnery gave the Royal Navy the edge. A gun crew of six to eight could fire three shots from their heavy guns every five minutes, the French and Spanish could only manage one pop gun eight-pounder every four minutes. They probably stopped for lunch.

Being in the Navy was described as like being in jail with the added attraction of being drowned, so what else could kill you?

Drowning, or being lost at sea or wrecked claimed about 16% of them. Just over 6% died in battle, or more likely on the surgeon’s table (less than one man a day). Mainly by flying splinters as the oaken ships pounded themselves to pieces. (Dudley Pope’s figures of 1875 casualties are only for six sea battles.) Those are the deaths. It is amazing what trauma people can survive and rise above a handicap. My grandmother lost an arm in an industrial accident during the war. She carried it to the first aid station where everybody except her fainted. She wore a hook after that and took up needlework.

This leaves an astonishing 78% being felled by sickness. But if scurvy and smallpox were controlled, what was left? There was typhus, imported when the jails were emptied to swell the crews, and there was yellow jack. But one that might surprise you that we associate more with 19th century drawing rooms than a ship of the line...

The dreaded consumption, mate.

Up until then, it had killed one-in-seven people that ever lived.

Swooning poets going down with the white disease

Even with all that bracing sea air, the TB bacteria hung in the dark fetid quarters, spreading mainly from lungs to lungs in the ships where hundreds of men lived and worked for up to two years at a time. The space allowed for hammocks was 18 inches even in my day.

We think of consumption as a prevalent ailment of the upper leisured classes, especially poets and writers, going dead white and swooning away, clasping lace hankies to their foreheads. Indeed, it was known as The White Disease or The Romantic Disease claiming Keats at 25, Henry David Thoreau at 44, Emily Bronte at 30. But history does not include the millions of ordinary working-class people crammed into the slums of the Industrial Revolution. Escaping from these foul conditions, sailors brought the infection aboard their ships. In the US, Doc Holliday, the dentist turned gambler and gunslinger, survived being shot at the gunfight at the OK Corral but died from TB in the high clear air of Colorado at 36. His long-term girlfriend, the charmingly named but quite attractive Hungarian-born hooker, Big Nose Kate, did not contract it from him and died at 91, just three weeks before I was born. Remarkable, when it claimed all four Bronte sisters and their brother living in that one rectory.

Treatment against TB was only developed in 1921 when an oral preparation was proven successful. It was in 1943 that Selman Waksman discovered streptomycin which was tried on the first human patient in 1949. However, there was no immediate widespread vaccination against TB in children as there was for smallpox.

But I probably already had it by then...

There were 800 of us at our grammar school and in 1954 we were all lined up and vaccinated in the arm. They probably used the same needle for all of us back then. They certainly did at primary school where it sat in a dish of alcohol. A week later, everybody came up with an itching lump at the site of the vaccination, except for four of us. We were just told to sit in the corridor while the other 796 (the school was big on teaching sums) were vaccinated again. We four thought we were isolated because we were infected and were all going to die. We were all trying to be brave, sitting on Death Row with the prospect of an early demise at 13. Then a white coat with squeaky shoes approached us with a needle. We four had natural immunity he said, and he wanted to take samples to help with a vaccine. Why didn’t you tell us???

Quirky on death row

It was only recently after a chest x-ray that my doctor told me I had been infected with TB as a youngster. Researching this article has given me a clue on how I might have contracted it. When staying at my grandfather’s riverside fishing shack I used to collect warm unpasteurised milk from the farmer in a jug, straight from the cow... I am not alone. Despite the school only having a 0.5% infection rate (see, I did pay some attention during sums), the World Health Organisation says over 10 million people fall ill with TB every year and 1.5 million die, making it the world’s most infectious killer. Amazingly, one quarter of the world’s population is infected with TB bacteria, but only 5-15% will fall ill with the disease. Just like at school.

Quirky experiments with centrifugal force while bringing home the unpasteurised milk which may have given him TB

If you catch it, a long sea voyage will not cure it and, as we have recently seen, the internal air conditioning of cruise ships ensures that what goes around comes around. Early treatments were quite lengthy, I knew someone whose TB lung in the fifties required a full year in bed. Modern antibiotics will kill the infection in six to nine months.

So, at the end of The Hound of the Baskervilles, when Sir Henry is advised to take a long sea voyage to repair his health, there should have been one proviso: Just stay on deck.

Don’t go below.

Sir Henry Baskerville recovers his health on deck