Sailor's Bluffing Bible - Sailing Holiday

Book Extract

Sailing Holiday

Before letting you loose on one of their expensive yachts, a sailing holiday company will need some idea of your level of competence. This is probably the only time in this book that we don’t recommend a mega-bluff: if your only qualification is Day Skipper Theory (failed) it’s probably best to admit it now, before you find yourself losing what’s left of your nine lives.

In general there are two types of yachting holiday: chartering or joining a flotilla. Alternatively, if dinghies are your thing you can try a dinghy sailing week.

Chartering

Chartering is just another word for hiring a yacht.

If you’re taking the boat without a professional skipper, this is a bareboat charter (don’t get too excited, nudity is not part of the deal). It follows that you’re going to have to do everything yourselves, so it’s worth mentioning the skills you simply must have within the crew:

You must have someone who can handle mooring lines. If you can’t throw a rope to a helper ashore, then docking in an offshore wind is going to be a nightmare.

Getting the sails up and down is relatively straightforward, but you must know how to reef both the genoa and the mainsail. Keep a lookout for wind arriving and reef early to reduce the sail area. If the wind drops don’t shake out the reefs too soon: have a cup of tea and see if the wind really has gone down.

Navigation is important. You need someone who understands a chart or at least realises that you want to stay on the blue bits and avoid anything coloured green. Remind them that hitting a rock at full tilt can ruin your whole day.

You need a method of getting weather information for the local area such as the internet, VHF radio or Navtex. If you can access it from your bunk so much the better – if the weather is going to be atrocious, you can just turn over and go back to sleep.

Someone should be able to operate the VHF radio and send an emergency call. This reaches all boats that are in range, but the flip side of this is that no conversation is private.

Things break and go wrong all the time on a yacht, so someone is going to have to fix them. The main culprits are the engine, the heads and the electrics. So ideally your crew will include a mechanic, a plumber and an electrician. If not, you’ll find that many people who have never even banged in a nail seem quite at home in the bowls of the boat changing the engine oil or replacing the toilet pump. This is one of life’s mysteries.

Anchoring is a key skill. You can drop the kedge (the small anchor) for lunch on a calm day or drop the bower (the big one) to hold you at night. Whichever you use, make sure that the inboard end of the chain is firmly attached to a strong point. Otherwise the whole lot may go to the bottom. As exemplified by the following radio exchange between a punter and the charter company:

‘Hello. Can you come over please, we’ve got a problem. Over.’

‘Can you say what the problem is? Over.’

‘Yes, we need some more anchors. Over.’

‘But you’ve got two on board. Over.’

‘No, we’ve used both of those. And there’s five more days to go...’

Lastly, have a few games up your sleeve to keep the crew happy when a trip gets boring. If it’s sunny and everyone is in swimming togs, rig up a plank across the foredeck and out over the water and see who can ‘walk the plank’ to the end. You’ll be surprised how difficult this is, and watching other people fall in the water always raises the spirits.

Flotilla sailing

A flotilla is a group of yachts – usually 2- to 6-berth sloops between 28 and 40 feet long – that sail together and are headed by a lead yacht with a professional crew. They are trained to spot a bluffer, so be on your guard.

Each day starts with a briefing on the day’s route, the weather and anything interesting along the way. The yachts then sail together or separately to the same destination and tie up. The lead boat usually arrives first and helps the yachts moor together.

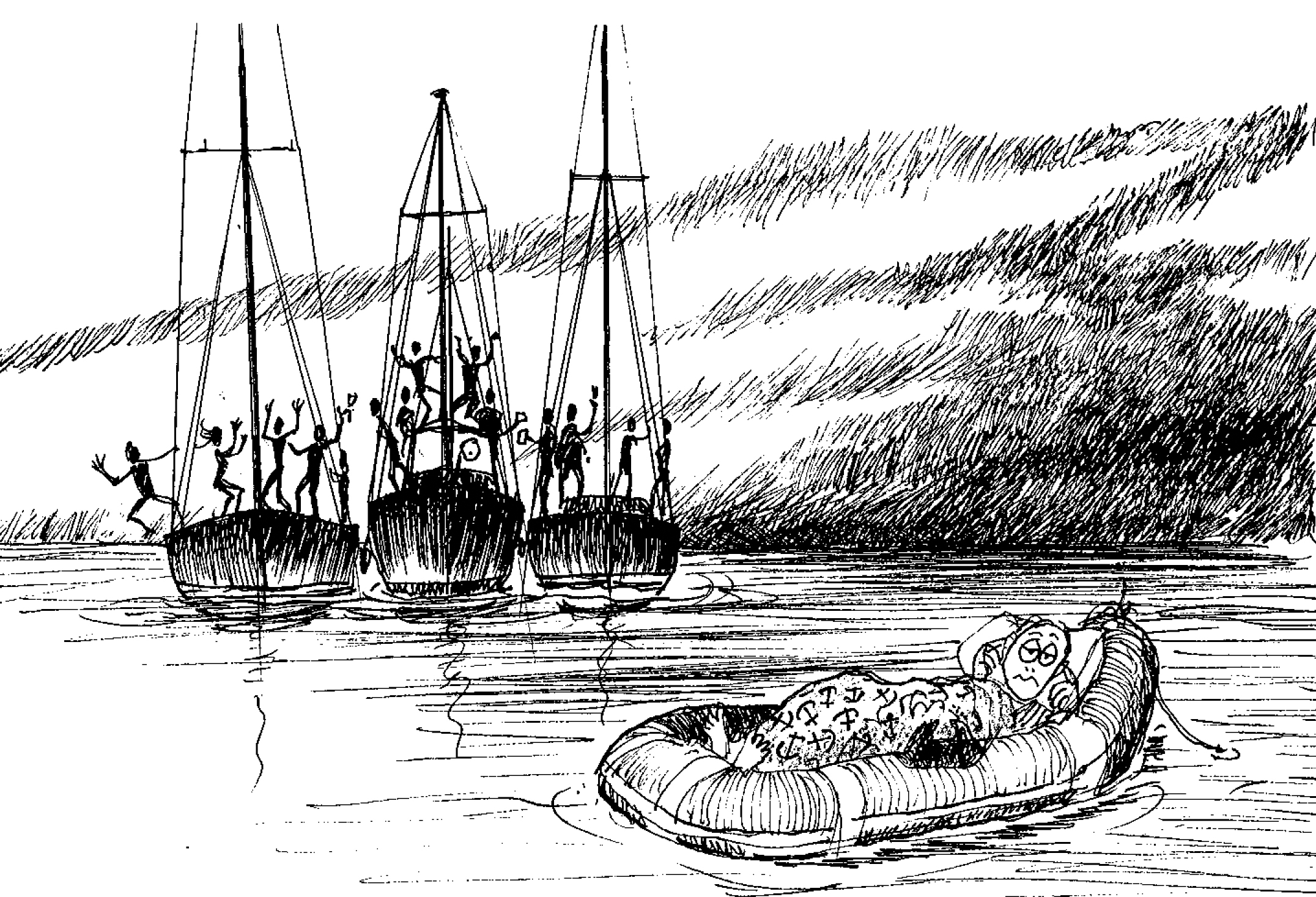

A pecking order will gradually develop among the sailors, and it’s essential that the bluffer emerges at the head of the pack. Since your sailing is suspect, aim to shine in the evening: make sure you have plenty of booze on board and can generate loud music and yours will become the go-to boat for preprandials.

It’s fun to see how low in the water a yacht becomes as more people pile on deck, entertaining to heel her by all moving to one side, and hilarious to watch the pontoon become awash as they all stand on it. But a wise bluffer knows his limitations, so head ashore for dinner before you reach the irresistible stage, or actually damage the yacht. You do have to sail her tomorrow.

Mooring Stern-To

Many flotillas sail in non-tidal waters where the form is to moor at right angles to the jetty, with the stern almost touching it. You then extend a plank from the boat to the bank and walk ashore.

The tricky bit is getting the yacht into this position in the first place.

This is what should happen:

- While well off the dock prepare a long stern line on both the port and starboard sides.

- Lower fenders on both sides of the yacht.

- Get the anchor ready at the bow.

- Explain what each person is going to do.

- Choose your target spot on the jetty and try to encourage someone ashore to stand there to take your lines.

- Reverse towards the target at a reasonable speed.

- When you’re three or four lengths away, drop the anchor and let the chain run freely as the boat reverses in.

- As the stern approaches the dock slow down and ‘check’ the anchor chain. The boat will stop.

- Throw the stern lines to the helpers ashore. They should cleat them either side.

- Adjust the stern lines and the anchor cable to hold the boat firmly just off the jetty.

- Set up the plank and send someone across it to bring back cold beer from the taverna.

This is what does happen:

- The boat motors in too slowly and a crosswind blows her sideways onto the next yacht.

- The helmsman panics, puts the throttle the wrong way and rams the dock.

- The helper ashore is nautically challenged and fails to catch either shore line, then falls in trying to retrieve them.

- Your anchor drags as the strain comes on it, so you have to go out and start again. (But your anchor line is twisted around other anchor lines, so you can’t.)

The Yacht’s Dinghy

On flotilla you will use the dinghy a lot more than you would in home waters. A dinghy in use is a good, practical way of getting ashore. Otherwise, the dinghy is a pain in the neck. Where are you going to put the wretched thing? You could inflate and deflate it every time, but this is tedious. You could tow it, but this slows you down. If there’s any wind it’ll skit about and may even flip over. (You can prevent this problem by putting your most loquacious crewman in it and letting out the towrope to its full extent.) You could lash it onto the foredeck, but it really gets in the way there (think bouncy castle in a small living room). Or you could pull it up the stern of the yacht and tie it to the backstay. This does get it out of the way but blocks the view astern – just when you should be keeping a lookout for large, overtaking ships.

Dinghy sailing holidays

At the end of a long winter why not kick off the new season with some dinghy sailing in the sun? If you choose carefully you should be able to find a venue with (almost) guaranteed wind, teaching for beginners and racing for the more experienced. You can try lots of dinghy classes and maybe have a go at windsurfing and SUP (Stand Up Paddleboarding).

Lasers

230,000 sailors can’t be wrong – the Laser is a wonderful boat. Start your holiday on one of these, choosing a rig (4.7, Radial or Standard – or ILCA 4, ILCA 6 or ILCA 7 in new money) to suit your experience.

The holiday staff will rig and launch the boat for you (don’t get too used to this luxury) and push you off. Lower the rudder, push down the daggerboard, and sail away. Reach up and down a bit to get the feel of the boat; tack facing forwards and only change hands on the sheet and tiller after you have settled on the new side of the boat. Once you feel confident try a beat to windward, a run and a gybe. Now you’re really flaunting it!

All boats have their quirks and the Laser’s is that the sheet can catch round the back (strictly the quarter) of the hull. You can score some good bluffing points by telling your listeners that this is caused by the sheet being too slack – it then falls into the water, is washed aft in the boat’s wake and catches round the stern when it’s tensioned again. Continue thus: ‘To prevent this I always wind in the sheet as I tack. For gybing I get going flat out, pull in an armful of sheet, heel the boat to windward (to lift the sheet up, away from the water) and give the sheet a tug as I turn. In one flowing movement, naturally.’

Of course this is pure bluff and, if you are not to be rumbled, you’ll need to go out behind an island and practise. A couple of days should do it, and after that you’ll need a holiday.

The only other danger point for the bluffer is landing, particularly on a lee shore (the wind blowing onto the shore). Here the Laser is brilliant – you simply untie the knot in the end of the mainsheet, let the rig blow downwind like a flag, and drift ashore – pulling up the daggerboard and rudder just before they hit the bottom. Don’t forget to drop the details of this technique into the conversation later, for extra bluffing points.

Other Dinghies

Some companies offer you the chance to sail a Waszp. This is also a single-hander but with wings to sit out on and foils underneath to lift the boat out of the water. The best advice has always been that you shouldn’t sail anything you can’t spell. And even if you can, it’s not a boat for the bluffer. And if you do bluff yourself onto one, make sure you wear a crash helmet.

You may also be offered two-man boats to sail, and this is a good idea since you’ll have someone else to blame. Alternatively, take one of the instructors with you ‘just to polish up your more advanced skills.’ Get them to show you how to handle an asymmetric spinnaker, for serious bluffing later: ‘So much easier than a conventional kite. You pull one string and the pole goes out and the sail up at the same time. To gybe you just pull it round with the sheet, like a big jib. And you pull it down with a retrieval line. The only real problem is what angles to sail downwind.’

Windsurfers

On a windsurfer you use the wind to reach, run, beat, tack and gybe. So far so good, you have mastered these evolutions in your dinghy sailing. But in other ways windsurfing is a new sport because you sail standing up, lean the rig to windward to balance the wind, and have no rudder or sheet.

The cleverest bit of a windsurfer is the universal joint (UJ) at the foot of the mast. It lets you rock the rig forward (which pushes the bow away from the wind) or aft (which pushes the stern away from the wind). This is how you steer.

The UJ also allows you to lean the mast (and yourself) to windward: your weight hanging down balances the force of the wind on the sail and powers the board forwards.

The wishbone is a bit like the boom on a dinghy. Since you have no sheet you pull the wishbone towards you to pull in the sail, and let it rotate away from you to ease the sail.

Windsurfing is simply (!) a matter of adjusting these three elements individually – a bit like rubbing your stomach and tapping your head at the same time.

Now let’s get the board sailing. Uphaul the rig out of the water. Lean the rig forward or aft until the board is aligned across the wind. LEAN BACK while pulling in the wishbone until everything is in balance. And off you go. If you want to turn into the wind rake the rig back a bit and pull in the wishbone a little. Once you are on course, go back to the original rake. If a gust hits ease out the wishbone, which allows you to lean back a bit more, then pull in the wishbone to its original position.

And so it goes.

Once ashore, don your Bermuda shorts and ‘Windsurfers Do It Standing Up’ T-shirt and head for the bar. For good bluffing points go through in detail that whopper wave your rode in: ‘I headed inshore in a trough, bore away and carved back off the top of the white water down the face. After working the wave to the max I duck gybed and sailed out through what was left of the wave. That wave doesn’t trouble me anymore.’ It helps if you have blonde hair and speak with a Californian accent, but do your best.

If challenged, switch the conversation to something you do understand, or fall back on that tried and tested prop used by any good bluffer, The Rant. This is pretty easy as windsurfers have plenty to be cranky about. They can’t have any fun unless it’s blowing Force 4 or above. However fast they sail, there’s always someone faster (the fastest speed for a windsurfer is about 60mph). And the cool guys have terrific names like Robby Swift, Antoine Albeau or Bjorn Dunkerbeck. What chance does a Pete Smith stand?

Stand Up Paddleboarding

SUP is the new kid on the block. Strictly, of course, it’s not sailing, but it’s the fastest-growing watersport in the world, and many holiday companies will have boards for you to try – and we are trying to make this book popular.

Compared with sailing, it’s not too hard. Climb on the board. Move to the middle and stand up with your feet either side of the handle. Face forwards. Hold the paddle with your hands shoulder-width apart. Rotate your shoulders so the paddle moves forward and put it in the water with the shaft vertical. Pull the paddle back through the water. Lift the paddle up when it gets near your feet. And repeat.

If you’re paddling on the left you may find the board turns right, so switch to paddling on the right to straighten up. But it’s better to go straight in the first place: make sure you’re taking short strokes with a vertical shaft and turn the blade slightly so it directs water under the board. That should do it!

At the bar the bluffer might mention a couple of paddleboarding cracker jokes:

‘How do paddleboarders avoid constipation?’ ‘They use SUPpositories.’

‘How do paddleboarders greet each other?’ ‘They say “What’s SUP.”’

A groan is the right response...