Sleep Management - Short-Handed Sailing

Book Extract

I do not like hardship. I sail for enjoyment and prefer the easy life. Being exhausted for days on end makes a fine story but not a good time. Some skippers sail with an informal watch system which more or less leaves the crew to decide for themselves who stands watch and when. Democracy may work for the occasional, short voyage but it can go very wrong. Time off watch is an important component of an enjoyable cruise.

Unless the short-handed skipper has worked out a watch-keeping system that strikes a balance between work and play, rest can be a pearl beyond price and every voyage a triumph of endurance over exhaustion. When I began single-handed sailing my thinking on fatigue management was a mixture of old wives’ tales, urban myth and downright ignorance.

One of my best misapprehensions was that any reasonably fit person should be able to miss one night’s sleep. Of course, I thought, there will be times they feel very tired, but a cup of coffee will deal with those occasions. In the real world, they will become progressively less alert and, towards the end of the 24 hours, it becomes easier to defer action than to take it. Staying on watch for 24 hours is possible, but it is not clever.

Another common myth is that, during a life or death crisis, individuals can survive two or even three days without sleep. This may have a grain of truth, but it means living on adrenaline and drawing on deep reserves of physical and nervous energy. Once the emergency is over, and the imperative to stay awake is removed, you collapse. Twelve hours’ rest, including eight hours sleep, are needed after staying awake for between 36 to 48 hours. Two- or three-days’ rest, including eight hours’ sleep each day, are needed to recover from three or four days of more or less continuous activity. This is not a basis for a regular watch system.

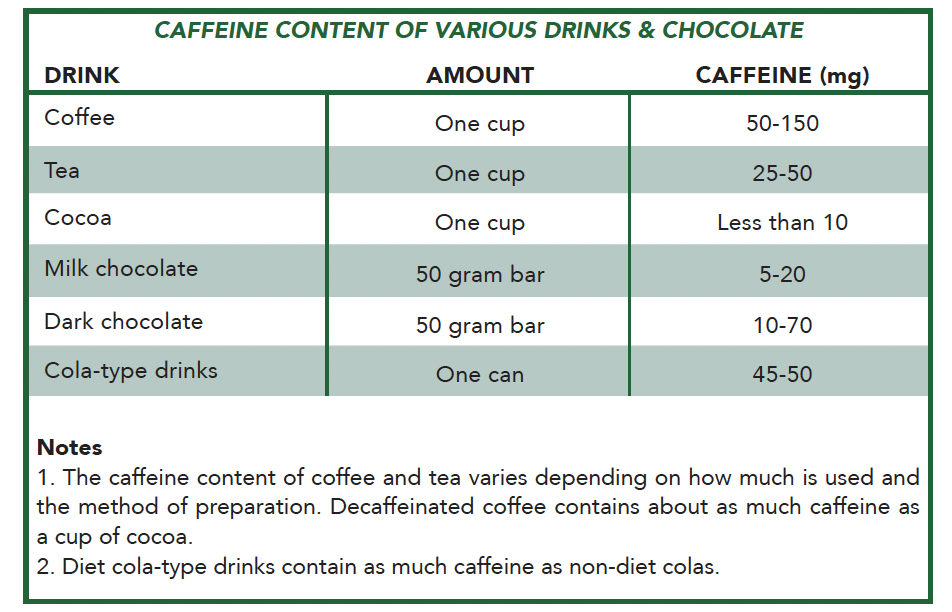

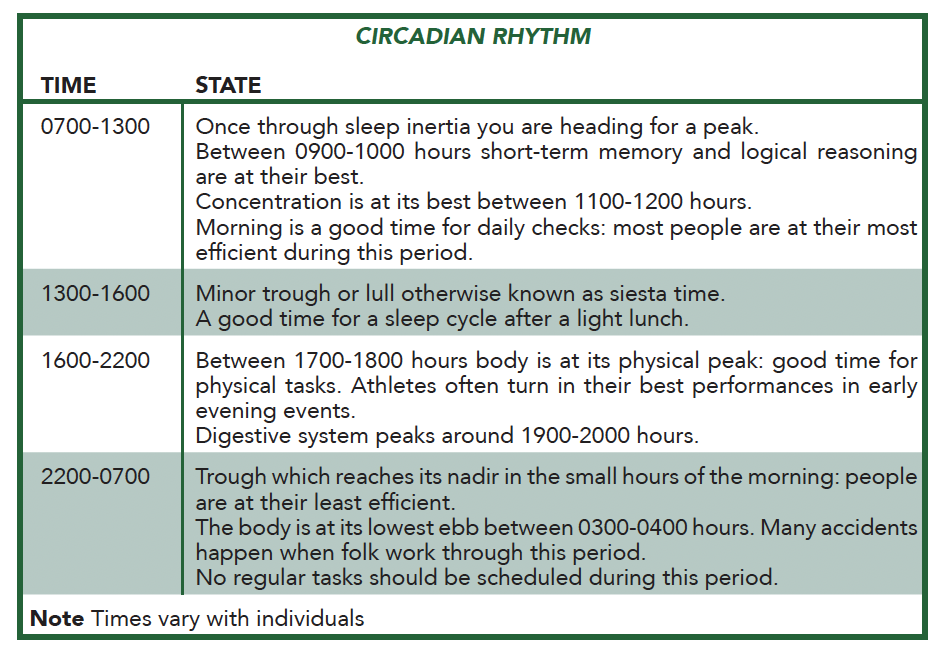

Nor are stimulants. Taking stimulants to remain awake appears superficially attractive, particularly in an emergency, but it is not recommended. Stimulants affect both mood and judgement. They work for only one or two days at most, after which you are finished for at least another couple of days. Caffeine is a stimulant and its consumption should be carefully controlled. There is some evidence that reducing caffeine intake re-sensitises you to its stimulant effects, so cutting caffeine consumption by at least half in the two or three days before casting off makes good sense. When at sea keep caffeine, in the form of coffee, cola drinks or tea, for the times when you have to work through a trough in your circadian cycle (biological 24-hour cycle). Remember, caffeine takes about 30 minutes to kick in and its effects last for three to four hours.

Do not drink coffee ahead of a sleep period.

Some single-handed sailors reckon that it is safer to sleep during daylight and organise their routine so that they work nights. This relies on believing that other vessels are far more likely to see you in daylight than at night. Since commercial vessels keep only a token visual lookout, I suspect that the odds on them sighting a yacht are about the same day or night and probably no higher than zero. It also assumes that you can reverse your circadian rhythm. You cannot. Your body clock is deep within your genes. Night shift watch-keepers are not as alert or productive as daytime watch-keepers because we are not programmed to work at night.

Anyway, under this system, unless you have fairly lengthy periods of sleep during the day before staying awake during the night, the problem of having enough of the right kind of sleep is not solved.

Other single-handers believe that they can train themselves to survive on less than their normal ration of sleep. While people differ in the amount of sleep they take each night, and this varies with age and physical fitness, if you consistently have less sleep than you normally need, then you will become tired.

The bad news for the older sailor is that, although you may sleep less, you are more quickly affected by lack of sleep and take longer to recover from long periods of wakefulness. Sleep stages 3 and 4, which are essential for physical restoration, tend to be shorter in older people. The good news is that you perform best in the morning.

The notion that fatigue is a state of mind that you rise above by the application of willpower, self-discipline or motivation is a gung-ho fable. Nobody beats the clock.

Fatigue is a physical condition brought on by a combination of total sleep loss, continuous hours of wakefulness (not necessarily the same as your total sleep loss), physical effort, environmental conditions and circadian time of day.

When these factors attack together then you become very tired very quickly and the chances of making a mistake, misjudgement or poor decision are unacceptably high. In laboratory experiments around a quarter of subjects display worrying declines in their performance after one day awake; no one has stayed awake for two days without displaying some drop in their performance. After two and a half days without sleep the performance of even the toughest, fittest and most resolute of subjects is seriously degraded.

I knew no better when I made my first long single-handed passage, but the gods smiled and decided to overlook what turned out to be a display of baseless self-confidence. I was sailing from Gosport to Cherbourg, a trip that I had made many times with a full crew. I reckoned that it would take about fourteen hours and, although on my crewed passages everyone stood their watch, having a solo watch-keeping system never occurred to me. I knew that I would be crossing busy shipping lanes and expected to spend most of the time in the cockpit.

I saw no problem in being up and about for the entire trip. Sometimes, my normal working day was longer than fourteen hours and I managed to stay awake without any special effort.

I was about to learn that when you sail short-handed then, on all but the shortest of passages, some form of watch-keeping system is essential.

Problems sneaked up and stabbed me in the back. First, even though I had discussed the weather with the forecaster in the Southampton Met Office, there was, contrary to expectations, an unexpected lack of wind. Second, I was short of fuel because I had forgotten to fill the tank. Lastly, I made the mistake of starting off in the evening after a day’s work. I had been up for nine or ten hours before I sailed. The tide pushed me to and fro as I dribbled across the Channel in great arcs and it was thirty hours before I finally reached Cherbourg. I had been awake through two nights and on my feet for over forty hours. It had been a tiring learning curve.