A New Approach To Offshore Design With Dick Carter

Book Extract

I had just skippered the yacht ASTROLABE to fourth in our class and sixth overall in the 1963 Fastnet Race. When the owner raised the question of how to improve the downwind steering on his boat, it was the first time I began to think seriously about the hull and rig. I always accepted these elements as fixed, as do most one-design sailors. My major emphasis, both in dinghies and ocean racers, had been on sails, tuning, tactics and boat speed. There was nothing one could do about the hull but clean the bottom. As the conversation intensified, I found myself finally agreeing to do a joint design for the 1965 Fastnet Race but a few weeks later I received a letter saying he had reconsidered and didn’t want to pursue the idea.

On the one hand, I was disappointed but on the other, I must admit, I felt a twinge of relief. In talking it over with a neighbour, he suggested I design my own boat. What a wild thought. Much as the prospect terrified me, I could not think of any reason for not doing so. But it took a while to build up the nerve. It was a test of my courage and, for that matter, a test of my character.

My first idea was to have the new design excel in light to moderate air, the most frequent weather conditions in the long distance race. My second related to windward performance. It made no sense when rounding a mark to go on the wind, strapping in the sails and sailing close to the wind, when the next mark is, say 50 miles away. So I was willing to sacrifice a bit of windward performance to gain more pure speed. The third idea was axiomatic. I wanted the new design to be a comfortable cruiser – light and airy below deck. To satisfy these three objectives, I came to the conclusion that a beamy, shallow-draft boat would do the job perfectly under the RORC rule.

I decided on a 24-foot waterline, the minimum length accepted by the RORC, and a 10-foot beam. I would name her RABBIT. I’d already named three dinghies RABBIT, but the name still attracted me. It suggested liveliness and speed.

The New Design – The Hull

I had been giving a tremendous amount of thought to the underbody. I wanted good downwind control. I also wanted a wine glass midship section, not only for increased stability but also for speed.

But it was the keel where I gave the most thought. The RORC rule had a shallow draft bonus – the idea being a boat with a shallow-draft keel would suffer going to windward and therefore deserved a reduction in rating. But I have long been of the opinion that in ocean racing, one should sail full on the wind rather than close. We made out like bandits with ASTROLABE in the 1963 Fastnet Race because we footed for speed. I ultimately decided that my new design would have a shallow draft keel of 4 feet 8 inches. It seemed to tie in well with stability gained by extra beam and was very compatible with my desire to sail relatively upright, dinghy-style, not to exceed 22°–24° angle of heel.

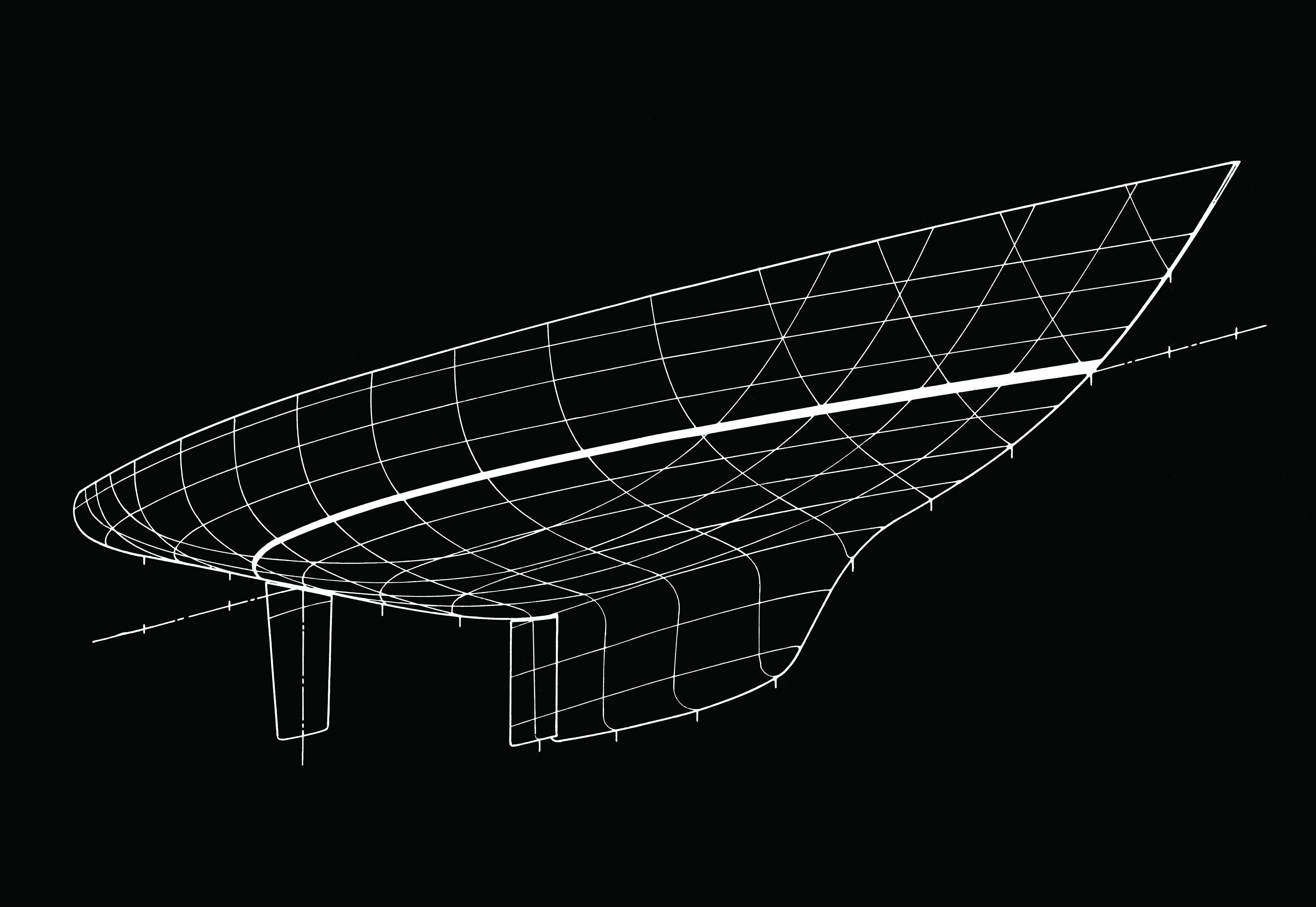

Axiomatic drawing of my new design, RABBIT

The Rig

I was determined to clean up the rig as much as possible. My goal was to reduce windage, doubly important because of my design objective to excel in light to moderate air. So I asked myself the question: if one could have halyards inside a dinghy spar, why not do the same for an offshore boat? I saw no reason why not. The mast would be as clean as clean could be. It would be a first.

The RORC rule favoured sail area in the foretriangle while penalising mainsail area. So I decided to load up on the sail area of the foretriangle with a maximum-size genoa. Since this permitted an extra foot of length on the spinnaker pole, I was able to get a 920 sq. ft. spinnaker on a 34-foot boat. I was not lacking in sail power.

One of the major advantages of less sail area for the mainsail was the shorter boom, only 12.5 feet in length. A shorter boom is also safer.

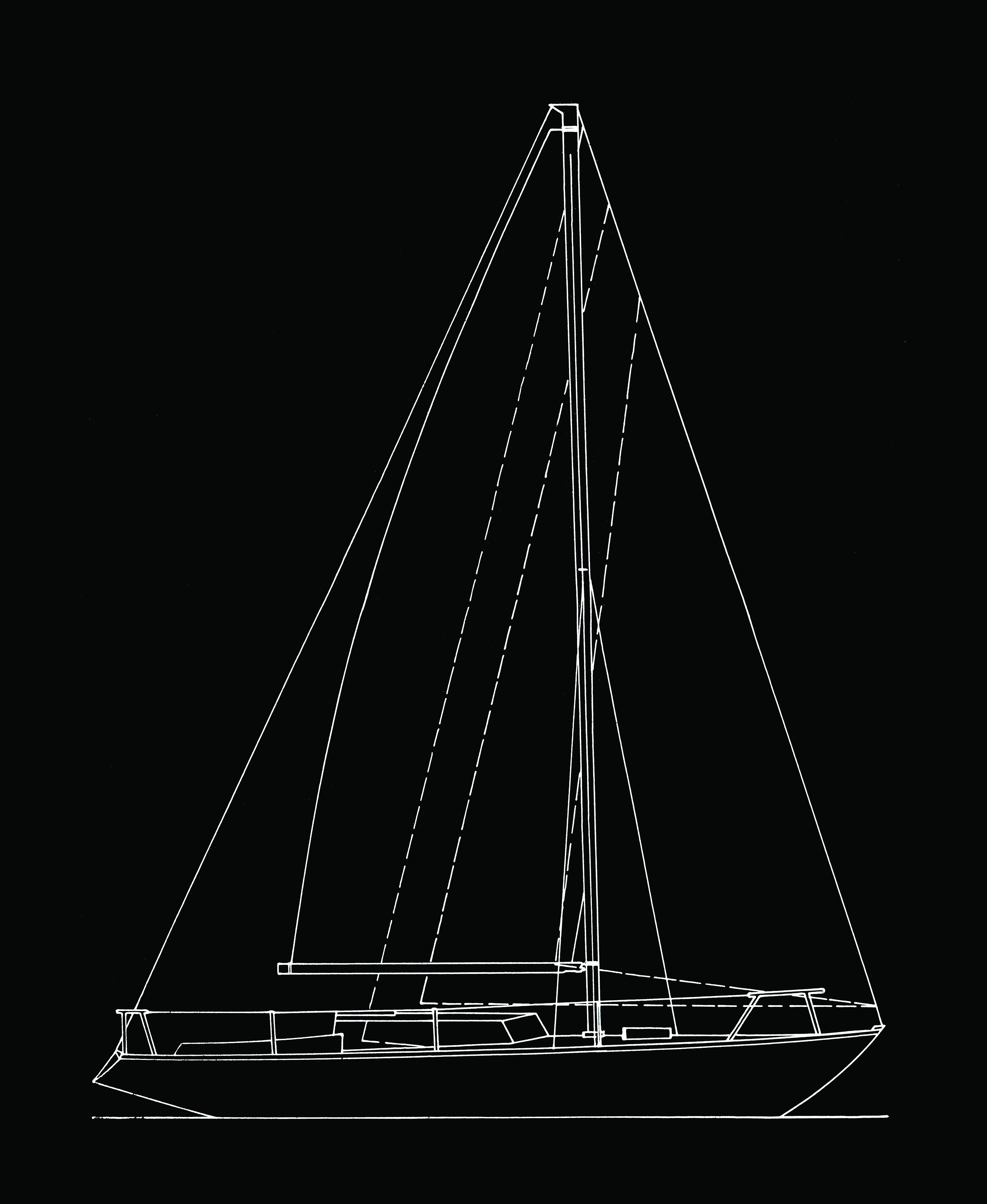

RABBIT’s sail plan with short boom

Aesthetics

I wanted RABBIT not only to be fast but also look fast – a challenge for a 34-foot boat. The sheer line should be crisp. My intention was to define it in a more vivid way by painting both the topsides and the bottom white, thus emphasising the navy blue waterline. Painting the bottom white would be a first in Europe.

A traditional stern looked old fashioned to me. But with a reverse transom stern, the stern’s sheer line can be parallel to the waterline, effectively giving the boat a more powerful look. An unintended consequence of RABBIT’S reverse transom was that it became universally adopted by other designers.

In May 1965, I eventually saw RABBIT for the first time. All I could say was, “She looks like a boat!” She looked better than I dared hope. As a novice yacht designer, I was of course pleased that my first project not only looked like a boat but floated like one, too.

The 1965 Fastnet Race

With 151 boats, the 1965 Fastnet had a record number of entries.

On August 7th, we had an evening start in a light to moderate westerly. What a contrast from two years ago, when a gale blowing Force 7 had made the start seem more like a survival course. Here we had a gentle breeze on a beautiful summer evening. It was an idyllic sight watching Class I and II sail away. Now it was Class III’s run for its 7pm start.

We elected to start at the Royal Yacht Squadron end of the line to minimise the effect of the ebb tide. On the line too early, we hooked back, found a hole, and hit the line at the gun. There was much short tacking in the scramble to reach Egypt Point, but once clear, we had a direct shot to the Needles and the English Channel. It was perfect RABBIT weather. In that light moderate air, and with our huge #1 genoa working to maximum, we sailed right past CAMILLE, the Australian Admiral’s Cup Team boat and the top boat in our 70 strong Class III.

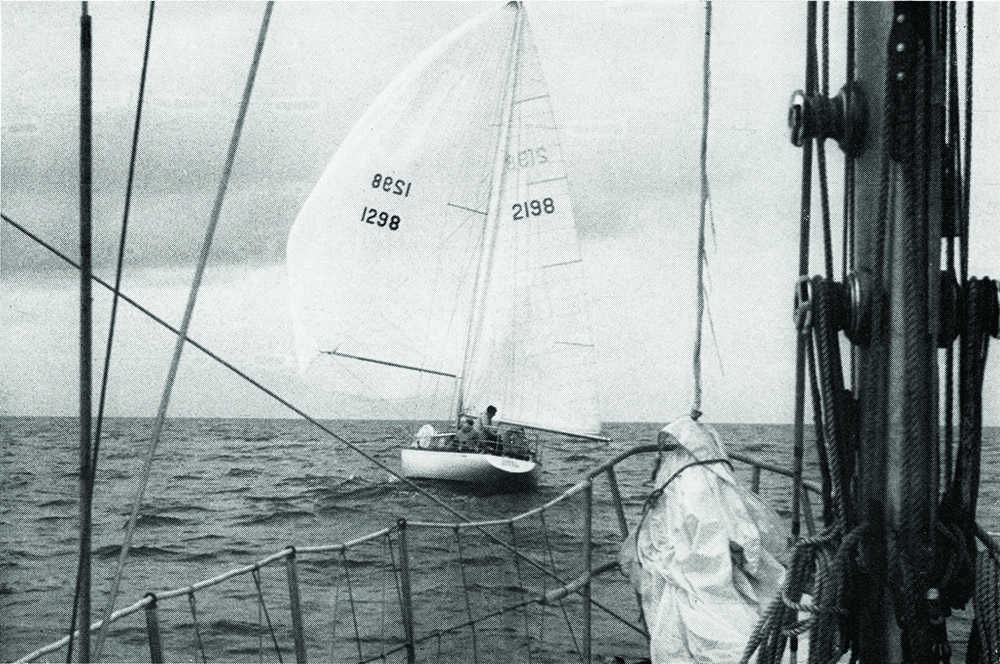

RABBIT at the Fastnet start

Although we rated 10th from the bottom, we started to sail away from the entire Class III fleet. I couldn’t believe it. Several times I repeated to myself, “This is the Fastnet and we’re pulling away from the whole class.” I had to pinch myself.

Once clear of the Needles, we set a course directly towards Portland Bill. Sometime during the night, I began to hear “Swoosh….swoosh….swoosh.” Out of nowhere, CAMILLE appeared and promptly slipped right by to leeward. Considering that she had a 30-foot waterline to RABBIT’S 24-foot, I was pleased that we had held her off for such a long time.

We made the Bill and our next target was Start Point, where the tidal current would turn against us early Sunday afternoon. In the light south-westerly, we were able to keep RABBIT moving at all times. We passed CAMILLE and arrived at Start Point just as the current was turning foul.

With our light air speed we squeaked through and sailed into Plymouth Sound. I knew that we were leading all of Class III, boat for boat. Moreover, they had to cope with the powerful, adverse current while we managed to keep moving in the light, fluky sou’wester until we were abreast of the Eddystone Light. Then we ground to a halt – no wind.

When the breeze returned, it came unexpectedly from the southeast. In a flash, most of our 18-mile lead evaporated. On the plus side, we had a perfect angle for the Lizard. It was ideal Rabbit weather. When dawn broke off the Lizard, our morale soared as we caught sight of a cluster of Class I and II boats.

Rabbit running with the spinnaker off Land’s End

After a day of running with spinnakers in confused seas, at 8pm, our wire spinnaker halyard chafed through. I went aloft on the genoa halyard to get us back in business. But not for long.

An hour and a half later, during a spinnaker knockdown, the spinnaker guy snap shackle broke, ripping the spinnaker in the process. We had no choice. We altered course slightly and sailed with the #2 genoa. In the morning the wind moderated some and I decided to gamble and set our half-ounce light air spinnaker, even though it wasn’t designed for this wind strength. Fortunately, it held and we carried it to the Rock.

When we rounded Fastnet Rock just before noon, we saw that we were in excellent company amongst many Class II boats. Only later did we learn that CAMILLE had excelled in that downwind leg and arrived at the Rock an hour and a quarter ahead of us. But we were first on corrected time over the whole fleet.

Sandy Weld patiently waiting for our action-filled rounding of the rock

We now faced a beat to windward to Bishop Rock, 150 miles away. Unlike most boats around us, I tacked to the south away from the favoured leg but the weather wasn’t playing to RABBIT’S strength. We shifted to our #2 genoa, when mirabile dictu, we got headed and the wind moderated. We suddenly revelled in ideal RABBIT weather again, shifted back to our big genoa and tacked for Bishop Rock. All day and night we sailed as fast or faster than all boats in sight. Unfortunately, as we approached the Scillies, we found ourselves having to beat to windward against a strong current. The fog didn’t help. We spent nine exhausting hours battling the current.

Nearing the Bishop, we were suddenly startled to see a boat emerge from the murk crossing our bow on starboard tack. It was CAMILLE! Unbelievable.

Finally, at 1:33 that afternoon, we crossed the finish line in brilliant sunshine. We motored into Plymouth and tied RABBIT up alongside other finishers. Then someone atop the retaining wall called down to us, “RABBIT, you’re second.” Almost numb with fatigue, I thought well, that’s not so bad. A few minutes later, the man returned and called down to us again, “RABBIT, you’re first overall!” I understood the words but I was too drained for it to fully sink in right then and there.

Although I never told anybody at the time, I had specifically designed RABBIT to win the Fastnet.

It was only the second time in the history of the Fastnet Race that a Class III yacht had won overall and it was accomplished in what was essentially a big boat race: Class I boats took 5 of the first 10 places on corrected time.

Winning the Fastnet fulfilled my design objective and validated my design ideas.

The winning crew

© Not to be reproduced without written permission from Fernhurst Books Limited.

Dick Carter: Yacht Designer is written by Dick Carter. Dick began racing small boats on Cape Cod and came out of Yale’s Corinthian Sailing Club as a champion. He raced International 14s and Fireflys before turning his hand to yacht design despite no formal training. He was highly successful and radically innovative – some of his ideas can be found on virtually every yacht today. After a decade of success, he left his yacht design career as suddenly as he had arrived. Many of his sailing contemporaries thought he was dead.