Your First Gybe With The Gennaker

Book Extract

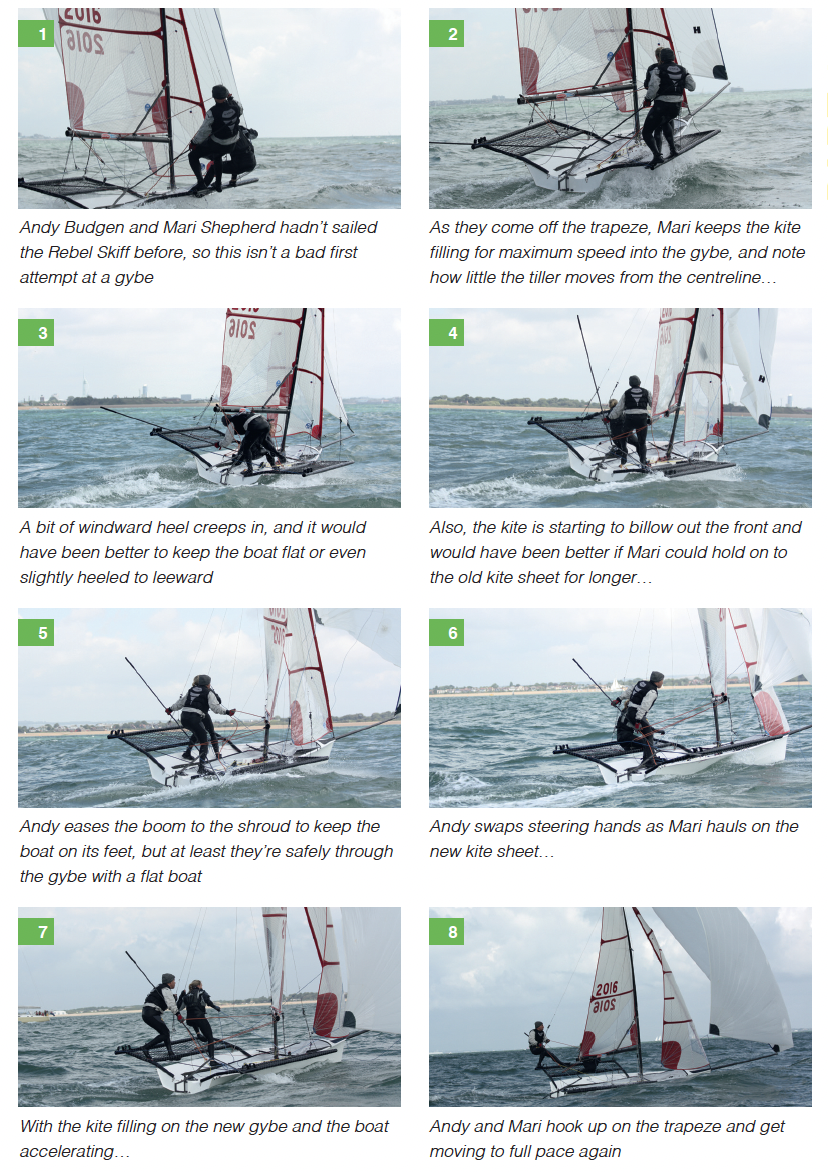

The rules for a successful gybe are very simple: keep it fast and keep it flat. Let’s look at the components of a good asymmetric gybe.

Not Too Much Rudder!

Gybing the gennaker is very different to gybing on a single- sailed boat or even on a boat with a conventional spinnaker. What takes most people by surprise is how little the boat needs to be turned to get through the gybe, particularly when you’re travelling at speed. One of the big mistakes for newcomers to asymmetrics is for the helm touse far too much rudder and to make too much of a handbrake turn through the gybe. In medium to strong airs too much rudder can result in you capsizing. Using small amounts of rudder has a big effect compared with gybing other kinds of boat.

Keep It Flat

The other difference from conventional dinghies is that it’s much more important to keep the boat flat throughout the manoeuvre. There’s little need for roll gybing, except in the very lightest of breezes. If you attempt a roll gybe in anything stronger, again you’re probably going to end up capsizing. You won’t go too far wrong if you can keep the boat flat all the way through the manoeuvre

Keep the boat as flat as you can during the gybe

Your First Asymmetric Gybe

First I’m going to assume that you’ve already done some dry-land practising, working through your footwork, body movement and hand movements, and that, as helm and crew, you’ve made a plan as to how you’re going to gybe.

Also, don’t give yourself the challenge of learning to gybe in a force five! Choose a light-to-medium breeze when you try things out for the first time.

So, here goes. As you’re approaching the gybe the helm needs to make sure that there’s space behind and to leeward before you begin changing course. You must make sure there are no other boats in your way and that you have a clear space to gybe into, because the direction changes are so much greater compared with conventional kinds of boat when they gybe.

Once you know that you’ve got space to gybe, tell the crew to get ready to gybe. If they’re on the trapeze (hang on, what are they doing on trapeze? This is your first gybe! One thing at a time, please), this might mean that they come in off the trapeze first so that they’re in a position to move through the boat as the gybe begins.

As the boat bears away, move your body weight to the centreline, keeping the boat flat so that, as the power in the rig decreases, so too does your righting moment. As the boom gybes across the middle of the boat, you should have reached the middle of the boat, with your head below boom height!

As the boat exits the gybe and gets on to its new course, crew weight should move smoothly and quickly to the new windward side of the cockpit, about the same time as you expect the boom to complete its arc and for the mainsail to start setting on the new side.

In full-power conditions, where you’re using maximum righting movement downwind, the ideal gybe is one where you spend the absolute minimum time in the middle of the boat. You want to be full hiking (or trapezing) on one gybe and into full hiking / trapezing on the new gybe with as little downtime as possible. Not only is this fast, it’s safer too. Lightweight asymmetric dinghies are like bicycles. Both are hard to keep upright when they’re stopped Keep the boat as flat as you can during the gybe or travelling slowly.

Timing Your Move

Whilst you’re learning the timing of all of this, there’s even something to be said for getting tothe new side a little bit sooner than you think you need. Better to get there too early than too late. The mistake that many people make is to get there too late, resulting in the boat gybing (a good thing) but capsizing almost immediately afterwards (a bad thing).

On the other hand, if you go through the boat too early, this can mean that the boat slows up too quickly and you never end up actually completing the gybe. The boom will never actually cross the centreline, which means that you might broach and capsize to leeward on the old gybe. This error tends to be the less frequent of the two so, if in doubt about your timing, move your weight over to the new side sooner than you think you need to.

You’ll soon gain in experience and confidence and feel ready to start gybing faster.

In planing conditions, you can even gybe with the boat slightly heeled to leeward all the way through the manoeuvre. If you think about it, that’s exactly what a windsurfer does when he’s powering through a carve gybe. The mast is always pointing away from the sailor (to leeward) and it’s almost as though the tip of the mast is fixed in space, with the board rotating around the tip of the mast. Fast asymmetric dinghies respond to the same treatment.

The Power Of The Battens

For sailors used to sailing conventional dinghies with soft sails, the surge of power created by an asymmetric dinghy can come as a shock. Part of the reason for this is that most modern asymmetric boats are equipped with powerful, fully-battened mainsails. When these stiff battens flick at the end of the gybe, they create a power surge that needs to be counteracted, and that’s why there’s an added incentive – compared with older more traditional boats – to get your weight onto the new side a little bit quicker. If you leave it too late, the power of the ‘batten flick’ can result in you capsizing, but if you get your timing right, you can harness the ‘batten flick’ to help accelerate you up to full speed on the new gybe.

The Measure Of A Good Gybe

We’ve already stressed the importance of travelling as fast as possible through the whole gybing manoeuvre. You know you’re gybing really well when the boom seems to float from one side to the other through the manoeuvre. In strong winds this is one of the sweetest differences between gybing a conventional boat – where the boom nearly always slams from one side to the other – and a fast asymmetric. Even if the wind is blowing 18 knots, if you’re gybing with 12 knots’ boatspeed, there’s only 6 knots of force moving the boom across. This is a great way of gauging your progress with gybing. The more the boom ‘floats’, the better you’re gybing.

© Not to be reproduced without written permission from Fernhurst Books Limited.

The Asymmetric Dinghy Book is written by Andy Rice. Andy is a championship winning dinghy sailor. A spell in the British Olympic Squad led him to sailing journalism – he now writes for a number of dinghy and yacht racing magazines including Seahorse, Yachts & Yachting, Yachting World and Sailing World. He is editor of the go-faster website SailJuice.com, aimed at sailors who want to improve their skills, and owner of Sailing Intelligence, a specialist media agency for the sailing and marine market.