Wetlands & Salt Marshes

Book Extract

As you progress up an estuary or venture behind sand and shingle spits, conditions change dramatically. Tidal flow and wave activity reduces, creating ideal conditions for wetlands – tidal flats, salt marsh, peat bogs, and reed beds. Tidal flats (also called mudflats) are coastal wetlands that form in the inter-tidal zone, and are created by the deposition of estuarine silts, clays and marine animal detritus. Being tidal, the flats are therefore submerged and exposed approximately twice daily, creating an unique environment for animals and plants. These salt-water ecological successions are called haloseres.

Tidal flats on the upper reaches of the River Deben near Woodbridge.

In the past, tidal flats were considered unhealthy places, fuelled by the belief that the ‘the miasma of the marshes’ brought disease and pestillence, and with good reason. The coastal marshes of eastern and southern England were perceived to be dangerous places, and deaths were unusually high in so-called ‘marsh parishes’, where ‘marsh fever’ and ‘ague’ (malaria) were endemic. This resulted in an epidemic between the sixteenth and nineteeth centuries, which resurfaced after the First and Second World Wars. The illness was probably caused by a northern strain of malaria, as well as tropical malaria. (The word malaria, incidently, comes from the Italian for ‘bad air’, mal aria.) Marsh parishes had such a bad reputation that only the poorest people would consider living there. One seventeenth century geographer noted that Upchurch, on the Medway estuary, ‘lies in the most unhealthy situation, close to the marshes’, and in nearby Iwade, ‘the stench of the mud in the ponds and ditches… contribute so much to its unwholesomeness, that almost everyone is terrifed to live in it.’

With no economic value and a danger to public health, marshes were often drained to create agricultural land. Today, the tide of public opinion has changed, and the estuary flats and salt marshes are now considered to be important ecosystems supporting large numbers of marine flora and fauna; they are also a key habitat in allowing tens of millions of wading birds to migrate from breeding sites in the northern hemisphere to non-breeding areas in the southern hemisphere. Wetlands are also important in preventing coastal erosion, and help prevent flooding.

Salt marshes generally evolve from tidal flats. As sediment accumulates, so the flats grow in size and elevation. As the area becomes higher, so flooding is reduced, and this allows plants to colonise the area. Plants reduce the speed at which the river or creek flows into the sea, and this allows more sediment to settle. As sediment and plant species increases, so more sediment is retained, and over time new plant species become established.

Twice a day, a salt marsh is flooded by seawater at high tide, and then drains at low tide. This combination of regular flooding and fine sediment creates an environment with low oxygen, called anaerobic conditions, and promotes the growth of special bacteria. (This certainly added to the general air of menace in the marsh parishes.) The mud in salt marshes often has strong pungent odour similar to rotten eggs (derived from hydrogen sulphide), and this is a clear indication of low oxygen levels in the sediment. Another indicator is the colour of the mud, which is normally grey / brown. If you slice vertically through mud in a salt marsh with a spade and black layers are present, this indicates the iron in the sediment has been chemically altered to form iron sulphide, and these areas have little or no oxygen.

The Blackwater estuary, Essex; the tide runs more serenely inside the protected mouth of an estuary, and this allows extensive mudflats, salt marshes and reed beds to develop.

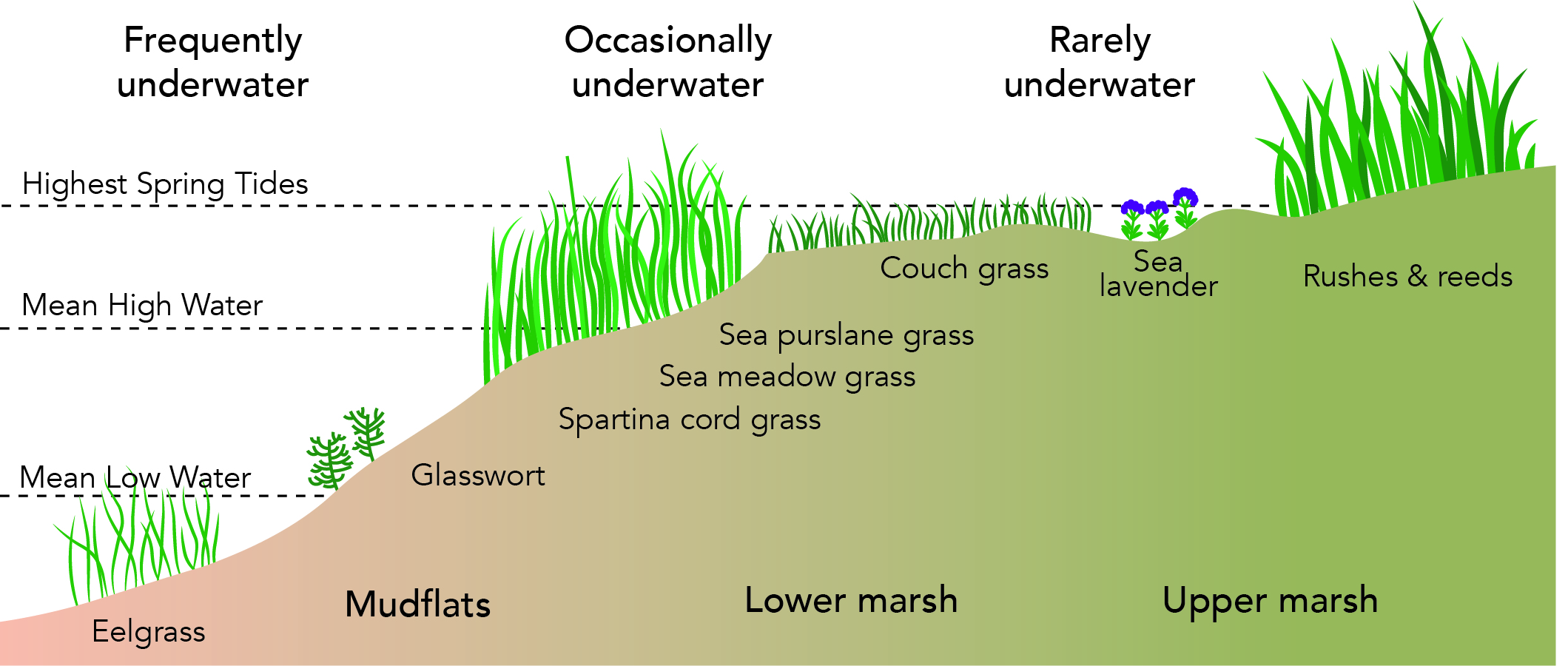

The regular flooding of salt marshes means the plants have to be very salt-tolerant, and species vary according to the degree of flooding. Plants growing on the lower reaches of the salt marsh – those parts which are covered by every incoming tide – need to be more salt-tolerant than those on the upper reaches, which might only be splashed by waves during high spring tides. This creates a clear zonation of plants, from the lower to the upper level of the salt marsh.

Salt marshes are zoned according to exposure to saltwater.

Microorganisms and tiny insects help break down the organic matter within salt marshes, and these then provide food for small fish, molluscs and crustaceans. During the flood tide, incoming ocean water brings nutrients into the area and takes plant material away during the ebb; this organic debris provides food for marine creatures offshore. On a rising tide, larger fish also move in and feed on the smaller species that permanently inhabit the salt marsh. Perhaps surprisingly, salt marshes are therefore one of the most diverse and productive ecosystems in the world. In them, rich organic growth is supported by nutrients coming down from the rivers, or flowing in from the sea. Organic production can reach 5 to 10 tonnes of organic matter per hectare (2.5 acres) a year, which is about the same as a field of wheat.

A salt marsh in Newtown Creek on the Isle of Wight at half-tide; the grasses are covered during high spring tides, and the creeks empty completely at low water.

The upper reaches of a salt marsh are colonised by reed beds, which are particually effective at trapping sediment and consolidating the salt marsh.

The Norfolk Broads are a unique area of wetlands in Britain, formed when rising sea level flooded Medieval peat excavations. Traditionally, the wetlands were drained by windmills (or, strictly, windpumps). The area is now a National Park and the country’s largest protected wetland.

Salt marshes and wetlands offer a wonderful opportunity to explore unique environments and to watch birdlife, and there are lots of sites around the British coastline to visit. The Norfolk Broads is the biggest wetland in the British Isles, and it is easily accessible – you can even hire a boat for a family holiday. Cley Marshes, also in Norfolk, has often been described as a mecca for birdwatchers, and the extensive lagoons and reed beds are home to a huge range of birds. A new visitor centre overlooking the marsh, run by the Norfolk Wildlife Trust, provides great views. Minsmere on the Suffolk coast is the showpiece reserve for the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), and is famous for the ‘Scrape’ – a man-made lagoon with shingle islands, and home to nesting gulls, terns and avocets. Here you can also see other key wetland species such as the bittern and marsh harrier.

In Scotland, the Caerlaverock Wetland Centre on the northern side of the Solway Firth is one of the best places in Britain to watch wild geese and swans, which take advantage of the relatively mild winters and plenty of food. Common sightings include barnacle geese from Spitsbergen, and hundreds of whooper swans from Iceland.

Brancaster Staithe in north Norfolk; here the salt marsh is protected from the sea by the dunes in the far distance.

The whooper swan (Cygnus cygnus) or common swan populations from Iceland regularly overwinter in salt marshes in Britain and Ireland.

Wetlands Safety

- These are fascinating places to explore and observe wildlife, but it is worth taking a few precautions:

- If you are alone, tell somebody where you are going and when you expect to return; always carry a phone, and remember the Coastguard can be called by dialling 999.

- As always, check the weather and be aware of a rising tide.

- Wear trousers and long sleeves as protection against spiky vegetation; insect repellent is also useful.

- Walking in marshy areas requires proper waterproof footwear which give good ankle support.

- Never walk without free hands, as you can easily lose your balance; a walking stick is useful to probe the area ahead and to check for quicksand.

- Wetlands are fragile ecosystems, so do not trample on sensitive areas and always respect nesting sites.

- Tidal areas are remote places and rarely visited, so you could always stumble on the unexpected; stay away from unusual-looking objects (which could be unexploded ordinance) and report the position to the authorities.