Traditional Position Fixing

Book Extract

Chapter 6 highlighted the fact that, having worked up an estimated position (EP), whether formally by plotting lines on the chart, or informally by looking around, the next action was to check the estimate and see whether or not it made sense. This is generally achieved by fixing the position. If the fix is by GPS, it is usually more than accurate enough for coastal or offshore navigation. Very close inshore, it may only be truly accurate within certain parameters which are discussed under electronic fixing. Most other fixes, while distinct positions, may or may not be closely defined. Evaluating the quality of a fix is an important part of the job of the complete navigator.

Whether you’re driving a car, a boat or a light aeroplane, GPS is established as the primary fixing system for Planet Earth. It is unusual now for a navigator to plot a fix on a chart from any other source. However, this doesn’t mean that the traditional methods are redundant. Perhaps the time will come when these arts are finally consigned to history, but electronics are not yet so reliable that we can afford to assume they are always going to be there. For this reason, and also to educate navigators in the art and science of their trade so that they can make better use of the more sophisticated electronic aids now available, classical fixing is still taught. The next part of this chapter is dedicated to these techniques.

Charted Objects

Whenever a fix is required, the first action is to check around to see if you are close to a charted object, such as a buoy. What is meant by ‘close’ will depend on how accurate you need to be, but if you are well offshore and within a cable (200 yards) or two of an object, you can consider your position more or less fixed. Such a fix would be defined as, for example, ‘1½ cables South of DZ3 buoy’.

Position Lines

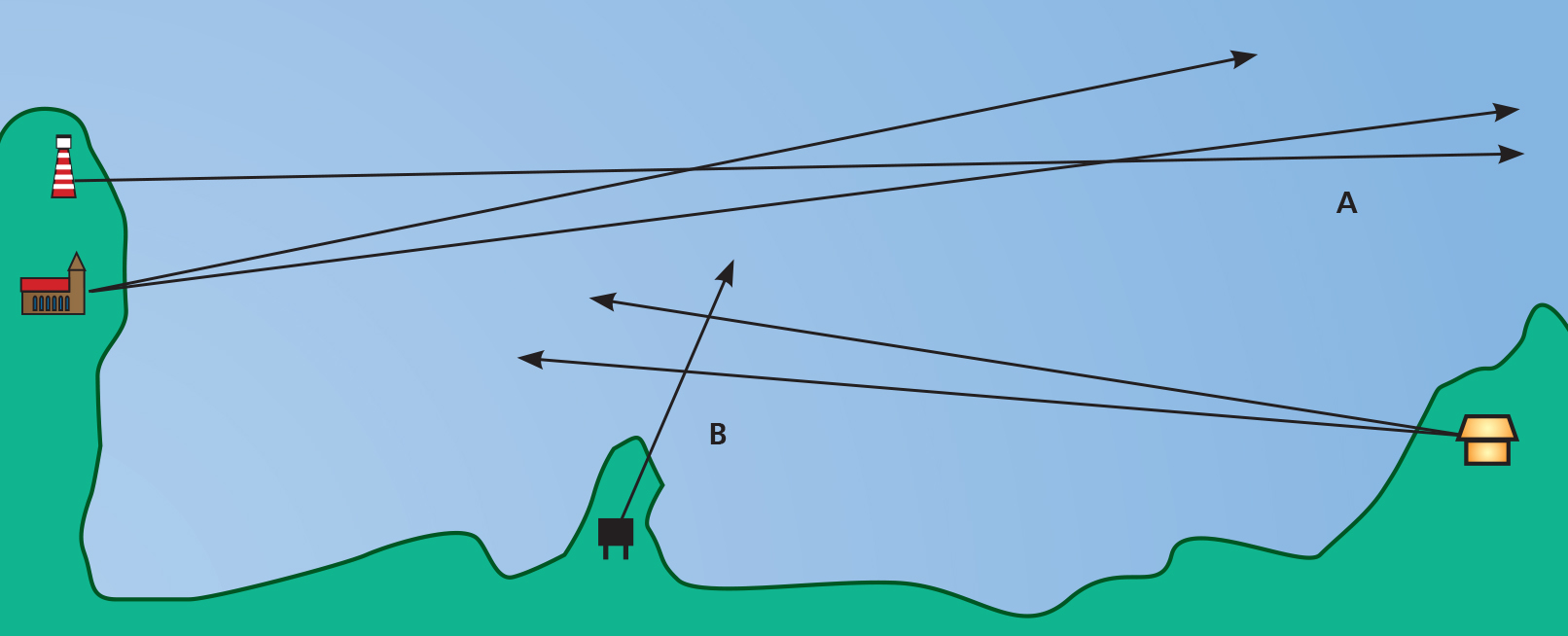

If there is no handy marker you’ll be obliged to fix using position lines (PLs) derived from charted objects that are further away. These should be selected so as to give the best possible ‘cut’. Note that PLs carry a single arrowhead at their extreme end pointing away from the object. This differentiates them from course to steer and courses steered because, in those cases, the single arrowhead falls around the middle of the line. Where two position lines cross at 900, for example, a 30 error in the bearing of one line will not throw the fix too far out. If the position lines are converging at 100, the results of the same error are catastrophic.

The effect of a 3° bearing error when the ‘cut’ is poor (A) and good (B). The Navigator at B can be much more confident in his position.

The effects of such errors are exacerbated when the objects are distant. A 30 bearing error on a nearby buoy will make little difference when you come to plot it on the chart, but a 30 bearing error on a lighthouse 6 miles away will result in a plot that is over a quarter of a mile out. If you have any choice, try to fix your position using closer objects. When three or more decent position lines are available, choose those that give the nearest approximation to a ‘cocked hat’ that looks like the example in Figure 7-2.

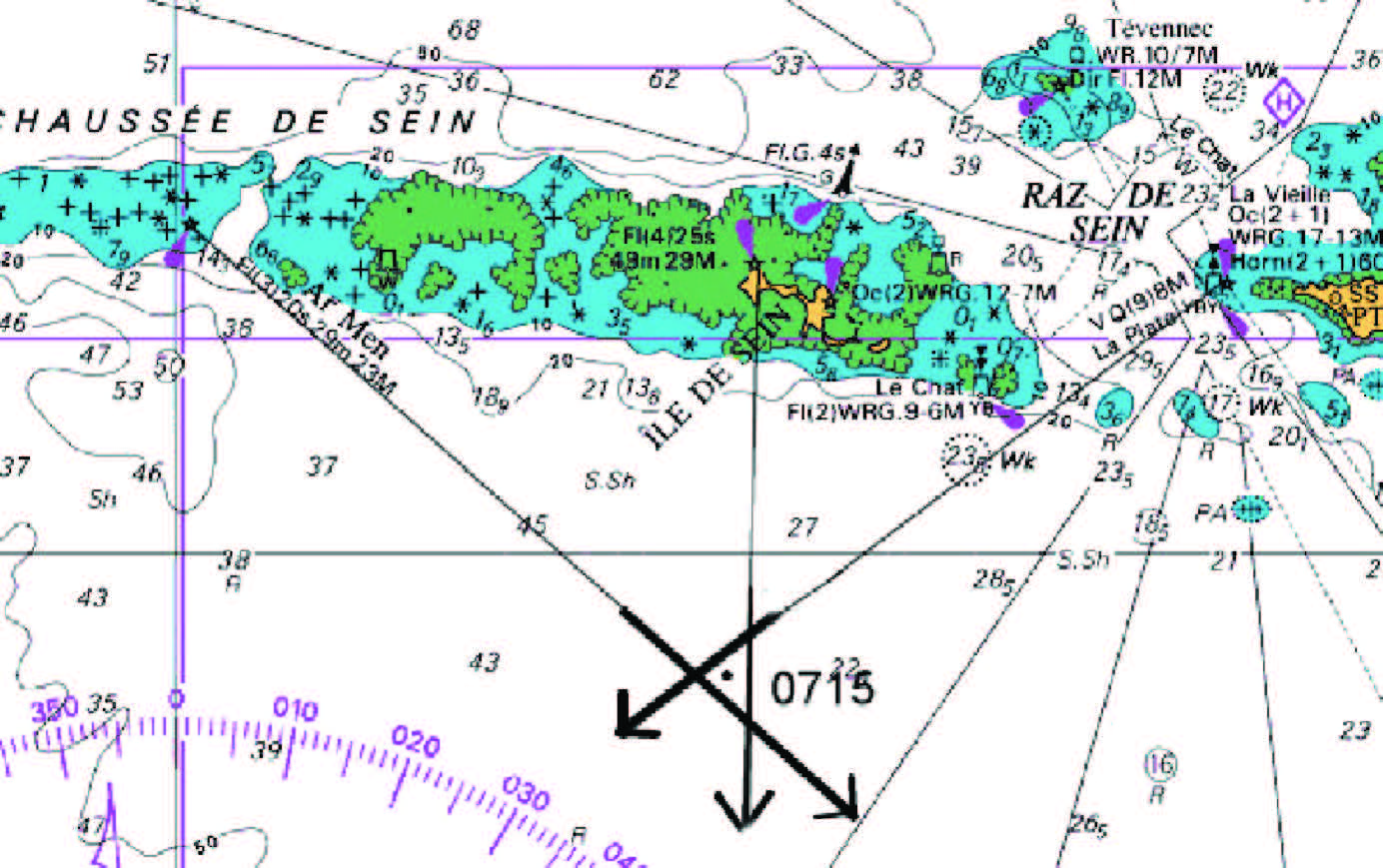

A cocked hat.

Note that the fix is defined on the chart with the time at which it was taken so as to refer it back to the log book. Note also that the PLs are short, neat lines. The light lines emanating from the lighthouses are shown merely to indicate to readers where the lines are derived from. In practice, they would not be drawn. Only the heavier lines of the actual fix are seen. This keeps the chart neat and so delivers maximum job satisfaction.

This cocked hat has a dot in the middle, which is the only practical answer if the position has to be defined in terms of lat/long. You could be anywhere inside the cocked hat, or even just outside it. The likelihood of actually being on the dot is slight.

If the bearings are such that the cocked hat is nice and tight, so much the better, but if the fix is enormous, then the best you have achieved is an ‘area of position’. Treat it with care and assume the worst. Better still, try a fourth position line to see if you can narrow things down – or scrap it and start again.

© Not to be reproduced without written permission from Fernhurst Books Limited.

Coastal & Offshore Navigation is written by Tom Cunliffe. Tom Cunliffe is Britain’s leading sailing writer. A worldwide authority on cruising instruction and an expert on traditional sailing craft, he learned his sextant skills during numerous ocean passages, many in simple boats without engines or electronics, voyaging from Brazil to Greenland and from the Caribbean to Russia. Tom’s nautical career has seen him serve as mate on a merchant ship, captain on gentleman’s yachts and skipper of racing craft. Tom has been a Yachtmaster Examiner since 1978. He wrote and presented the BBC TV series, ‘The Boats That Built Britain’ and the popular ‘Boatyard’ series.